May 09, 2009

ETF FAIL: Understanding Time/Volatility Decay in Short and Leveraged ETFS

There is a crack epidemic on the stock market. It trades by a variety of street names, FAZ, FAS, SRS, TZA & QID being just a few. Like crack cocaine these vehicles promise fast and stunning highs, one small hit can take you to the top. Occasionally they even succeed, but like crack cocaine these vehicles are doomed to collapse, each successive hit providing ever diminishing returns, lower lows that an addict believes they can only escape from via another hit.

Unlike crack there is nothing illegal about these things, they are short and/or leveraged ETFs. Exchange Traded Funds designed to replicate the effects of shorting various industries and trading with high amounts of leverage like the big boys do. ETFs are a very new concept to finance, they are basically mutual fund like entities that trade on the stock market, making them more liquid and more accessible to investors than mutual funds. They've been around for about two decades, but it's only in the last few years that they have really taken off in big numbers, with "innovative" short (aka bear) and 2x or 3x leveraged ETFs popping up left and right. Take a look at a chart for FAZ, the 3x Short Financial Industry ETF and look at the volume indicator on the bottom to get a sense how interesting in these things has exploded.

In 2008 leveraged bear etfs like FAZ were tickets to riches, as the stock market crashed they erupted in value, possibly making a few clever operators insanely rich. But that initial success quickly turned nasty. These ETFs are all flawed to the core, they are designed in a way that they decay over time, their values fluctuate up in down, but the overall tend is mathematically almost guaranteed to be down. The easiest way to see this flaw is the look at chart of a leveraged Bull and Bear pair over time. FAZ is a 3x Bear, it is designed to go up when financial industry stocks go down, and to return 3 times more than the value that those stocks go down. FAS is the 3x Bull counterpart, it is designed to go up when the financials go up, and to go up 3 times faster on a daily basis.

One would logically expect these two ETFs to cancel each other out, one goes up 3x when the other goes down 3x, so over time the net result should be zero. Yet if one looks at chart of these two mapped out over the past 6 months a very different picture is drawn. FAZ is down 94%, and FAS somehow is down too, by an almost as nasty 75%. Both are decaying rapidly taking their holders down to the bottom all because of a nasty mathematical quirk (or less generously flaw) in their design.

What's happening is volatility decay, these ETFs all lose value when the stock indexes they track are fluctuating up and down. The key to understanding why is a very basic mathematical fact relating to the way these ETFs are designed to reflect the daily percent changes of the parts of the stock market. The problem is that percents going up and percents going down don't always sync up, but instead have a distinct downward trend. This is easiest to see by looking at a 3x leveraged ETF. Lets call this ETF BSBS, and assume it's positively tracking the Bull Shit Index. When it starts both the index and BSBS are valued at 100. The next day the index goes up by 25% to 125. Now BSBS is designed to return 3 times that percentage or 75% so it goes up to 175. For a day at least it's a great investment vehicle. Now suppose the next day the index falls back down to earth, a 20% decline back down to 100. Well BSBS is now designed to go down 3x that or 60%. Now 60% of 175 is 105, a monstrous decline. The BSBS ETF is now all the way down to 70, while the index is still hanging in at 100. That's it in an essence, these things rise fast, but they fall even faster. It's that simple and that toxic.

The exact same thing is even truer with Bear ETFs. A non leveraged Bull ETF will actually have no volatility decay (although there are other smaller decays in their design). But the corresponding non leveraged Bear ETF will have a decay. Say you have a Bear ETP called UUPP designed to track the Bull Shit Index. Like BSBS it starts with both UUPP and the index at 100. Now say that the index goes down 25% to 75. Well that's why you bought UUPP, cause you wanted to sell that Bull Shit Index short and for a day you were right, UUPP goes up 25% to 125. Now the next day, the index doesn't behave and goes back up to 100, a 33.3% rise from 75. Well the index is back where you started, but was does UUPP do? It does down 33.3% from 125 to... 83.75. Yep, once again the ETF structure is screwing you. There is only one way in the end with these drugs and it's down.

Now one has to assume the ETF makers are well aware of these properties, yet they still sell the ETFs. Of course to protect themselves they warn the buyers, these ETFs are marketed as daytrader vehicles, things that should be bought and sold over the very short term, a few hours at a time maybe, if not a few minutes and a day or two maximum. Its a fair enough warning and not bad advice, but it's also a misleading warning. The reason is that there are circumstances where these ETFs are actually perform well over longer periods of time, and in 2008 we experienced some of these circumstances. Buying say QID (2x Short the Nasdaq index) in early 2008 and holding on to it for the year would have netted you a very healthy return.

When the stock market is trending very strongly in one direction, with very little volatility, just day in and day out moving the same way, than a leveraged ETF in that direction is going to produce stunning results. But stock markets rarely move smoothly, they stop, start, reverse, correct, roll sideways and then jump. They usually have some direction, but it's rarely and clear path, and it's the volatility that cracks you.

There is at least one more misleading thing about how these ETFs are framed as well, the way the term leverage is used. There are situations where an 3x "leveraged" ETF produces returns a similar result to being 3x leveraged (ie borrowing money to buy three times the amount of a stock than you have the cash for.) There are also situations where the results are quite different. Again it's the result of a basic mathematical effect/flaw in the ETF construction. Basically these ETF return numbers like classic leveraged situations when moving away from your baseline investment. However as soon as there is any reversion back towards that baseline the numbers begin to skew.

Say you have $100 that you want to use to buy XXX. But you want to make more money so you go borrow $200 more so you can buy $300 worth. That's classic leverage. If the next day XXX jumps up 25% to $125, well you now have $375 worth of stock and $200 in debt. Net result is being up $75 on a $100 investment, so you've made 3 times the 25% increase in the stock.

You could also buy XETF though an 3x ETF that tracks XXX. $100 worth, on day one would also go up 3x the 25% increase, so far so good, you've made triple profits without even borrowing money. Sounds a little too good to be true, no? It is. Cause say the next day XXX goes back to 100, a 20% decline. In the classic leveraged situation you go from holding $375 to holding $300. Minus your debt you are even (ignoring interest for simplicity.) Not great, but not bad either. But with the "leveraged" ETF, as we've seen before, that same 20% decline in XXX is going to have a different result. It will produce a 3x the percentage decline, so 60%. Now 60% of 175 is 105, so this ETF is decaying down to 70. Instead of being flat on your initial $100, like you would in a classic leveraged situation you are down 30. Just like a crackhead you just can't back to those initial highs like that can you?

October 24, 2007

Photoshop by Committee

It's easy to just say design by committee. The story behind the new New York City Taxi graphics reads like a text book case. A firm makes a design. The client gives feedback. A new look comes in. Another firm comes late in the game with a new design element. A powerful department rejects a design for intruding on it's turf. The result is a sloppy hodgepodge of elements. Designers are rather predictably lining up to critique it.

Personally I rather like it. NYC Taxis have always had a sloppy mix of design elements on their side. Anything cleaner and neater, anything better designed, would threaten the only design element that matters. The bright yellow color screams "New York Taxi" louder than anything millions of design and innovation consulting fees could ever generate. As long as the cabs stay yellow, those taxis will look the same. What will never look the same again is NYC.

The new taxis provided a bit of political cover for an even bigger design project. New York City has a new logo. The suddenly infamous Wolff Olins designed it. and the new NYC taxis are the first place most New Yorkers have been exposed to it. Those taxis are design by committee, but that logo is something different. You can call it Photoshop by committee. Get used to it cause you'll be seeing a whole lot more of it.

What happens when you have a committee where every single member has a copy of Photoshop on their computer? Or worse yet every member has a designer on staff? Design by committee once broke down to a bunch of opinions and needs, all sorted out by one or two designers. The committee stacked up its requirements, its problems and its bullshit, and the designer cooked it all up into some bland result. A designer in that situation today would feel blessed.

What happens in Photoshop by committee is far worse. The needs and the problems and the bullshit are still there of course. But then comes the designs. Not just from the designer, but from the committee members. From their staff designers. From their assistants. From their teenagers and toddlers. From their neighbors, coffee shop baristas and dogs. Committees were once additive, the members just piled on the guidelines and suggestions and the designer boiled them down into a result. Now committees are recombinant. They warp, splinter and evolve into competing designs. The designer is barely the designer at all. They are the person who must make these mutations all work together.

Design by committee is about making rules. Photoshop by committee is about breaking rules. It's often the only way the designer can get the multiplying designs to recombine. Wolff Olins' professional salespeople call this "container logos" and it seems to be winning them some super premium clients. Most of us would just call it bullshit, but we aren't the ones with the super premium clients.

In the case of New York City what this amounts to is a big old smudge of the letters NYC. Not surprisingly it looks a lot like design from the early days of Photoshop. A design from an era where designers had no idea how to use the powertools in their hands. It's ugly and clunky and has nothing to do with NYC beyond using the letters. I love it. It follows none of the rules of design that stifle the profession. It's loud and bold and will show up in all sorts of places. Like the full NYC taxi design it graces, it will never step out of the shadows of a far bolder design, Milton Glaser's classic I (heart) NY logo. Is it great graphic design? Not at all. But it is great Photoshop by committee and it will work just fine.

March 11, 2007

All Free

Freebase is exactly the sort of thing that you only take seriously once you know Danny Hillis is behind it. Hillis is a bit of an underground hero in a world where many of his nerd peers skyrocket to fame in the business press, if not in popular culture as a whole. A nerd's nerd, his best known company went belly up in the 80's, his current one flies well under the radar and the NYT article linked above introduces him by mentioning his time as a Disney Imagineer, although it's never been clear he did anything notable there. But that first company was years ahead of it's time, his slim book Pattern on the Stone is easily the definitive text on how computers actually work and his Long Now Foundation one of the more audacious and mindboggling non-profits around (and one in which I'm technically a "charter member".) So yeah, when Danny Hillis launches a venture, you know the nerds at least are listening.

Freebase is the latest in a long series of essentially failed attempts to transform information into meaning. Or more specifically to transform computer readable information into computer readable meaning. Many have walked that path before, and in the end there is only one real success story, but that success story was Google with their Page Rank algorithm that made them a success. And like Google, Hillis is starting this venture with the best of intentions, and like Google Hillis is already starting say things that should make you very afraid.

The rhetoric of Freebase is all about freedom, openness and sharing. Everything about it says this is for you, this is for free this for the good of the world. Yet with a simple turn of a phrase or perhaps a slip of the tongue, Hillis lets on that he doesn't just want to share a lot of information, he wants it all. “We’re trying to create the world’s database, with all of the world’s information,” are his words and they probably sound familiar to anyone who has read a bit about Google over the past couple years. Despite loudly saying "don't be evil" Google is known to talk about the goal of "organizing all the world's information."* A phrase perhaps better suited for a cartoon supervillian than a large corporation.

The all might sound innocuous enough at first, until you place it into the context of Google's own actions. Perhaps you have a Gmail account, or at least send emails to someone who does. All the worlds info includes everything on those emails, do you want Google organizing all that information? The Gmail terms of service originally indicated that emails you delete might not actually be deleted off their servers, does that make "all the world's information" sound a little different then before? Some information is meant to disappear, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. Google it seems is not willing to make that distinction, although ironically they more than any other entity have the power to make things disappear. Instead of a situation were information is either available or not, we are creeping towards a world where information is either available through the front of Google, or it's only available the back, to those who can move through the backdoors of their databases.

Now I'm a huge fan of Hillis' work, and on a certain level Freebase is designed precisely to mitigate some of Google's emerging database monopoly, yet it's pushing forward with the exact same hubris that has made Google's "don't be evil" mantra such a sick joke upon the world. The rhetoric of freedom and openness may sound as universal as "all the worlds information", but it speaks to humans, while the information gathering is done by Turing machines. Hillis and the Freebase team are probably genuine in their interest in doing something for the world, but in the end they can only represent the interests of those that share their tech forward beliefs. Nestled safely in Silicon Valley it's probably easy to think the whole world shares those sentiments, but nothing could be further from the truth. The result it seems is a strange incubator where the supernerds slowly morph into supervillians, bent upon conquering the world (of information.)

*Google seems to have backed off this as public stance of late, but it still pops up on their site in places like their corporate philosophy page.

February 19, 2007

Symbolic Action (In Defense of the New Radiation "Symbol")

Well next time you see that sign a coming you better run. It's a new supplemental symbol for radiation danger, commissioned by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and designed to convey danger in a more intuitive way then the traditional radiation "trefoil". Now the interaction designers over at Adaptive Path are absolutely turding all over the results (and Michael Beriut just sighs), and in many ways they are right, it clearly is the result of design by committee and there is nothing elegant nor simple about symbol they generated.

Then again, there is nothing simple nor elegant about dying from radiation poisoning is there? And to ask the IAEA and ISO to do anything but design by committee is akin to something in between asking for a complete redesign of international relations and the impossible. To accuse them of design by committee is a completely valid statement of fact, but it's also a rather impotent critique. To ask them not to design by committee may be fantasy, but we can very reasonably ask and expect them to design by committee the right way (or at least in one of the right ways) and with the new radiation symbol that appears to be be exactly what we got.

Now I have a lot of respect for Adaptive Path and I'm sure with the appropriate time and resources they could produce a symbol at least as good and most likely better than what has been created. In that process one of the first things they'd probably learn is something that is clearly not evident their current critique, that it is radically more difficult to create symbols that invoke action then it is to create symbols that describe objects.* At least at this juncture in time signage symbols are inherently static, solid and rigid. To transform a static, solid or rigid object into a symbol, is a relatively straight forward act of abstracting the objects characteristics into lines shapes and colors. Some objects are easier to work with than others, but all at least possess tangible starting points to abstract from. Verbs however are by there very nature intangible, and more difficult to capture in abstraction. When the goal is not just to encapsulate the verb, but actually trigger it, to create sign that does not just represent but actually creates an action then the challenge is exponentially harder, and that is exactly the challenge the IAEA and ISO were faced with, creating a sign that does not just warn people, but actually causes them to turn and run for their fucking lives. Not exactly the easiest task.

There is one sign that is radically more effective at creating action than any other, and that is the stop sign. Part of it's effectiveness is it's ubiquity, it many cultures you can find the stop sign just about everywhere, so it's easy for the meaning to get ingrained. The red color helps as well, but ultimately the stop sign is successful because all symbols are stop signs. Often it's more of a mental stop then the physical stop, but one can not process a symbol unless one pauses for microsecond and then reads it. When one reads the stop sign one has already begone the process of stopping, all the sign does is say continue on through with the stopping process. No matter how fast one might be traveling as soon as one actually sees the stop sign there is at least a little bit of inertia going into the act of stopping.

What this means in terms of making signs like the radiation symbol designed to induce action, is that task is even more difficult. Conveying an action in static is hard enough, and getting people to follow through and actually do the action it is exponentially harder, but on top of that the very fact that the message is embedded a symbol is invoking the exact opposite effect, causing the reader to pause and stop for at least a second before hopefully doing a 180° turn and running away. And it's this challenge that the committees of the IAEA and ISO were faced with as they went about designing their new symbol.

The result is indeed neither very elegant nor simple, but it is in fact I think rather effective and quite interesting.** Rather then produce a symbol as they claimed to have done, they actually produced something rather different, a small comic, five symbols sequenced to invoke an action. It's actually a rather innovative solution, something which contrary to the Adaptive Path post, you actually would not really expect to emerge from a committee in action. For if the goal is to create an action, a static symbol is not the right way to do it. But by creating a microcomic, a sequence of symbols, what emerges is not just a static sign, but a sign filled with action, filled with invisible gaps between the actual symbols, gaps that the mind fills in with actions. Gaps that turn the static noun of a flat still piece of signage into an active verb, a true call to action. It might not be the best looking sign but it pretty clearly warns far better than then old abstraction of the "trefoil." So there you have it, read the signage on the wall and get the fuck out of here ; )

- This lack of distinction is clearly apparent in the hypothetical symbol for taxi that is used as a rhetorical device in the Adaptive Path blog post. A taxi is of course an object, a noun, while running from radiation is an action, a verb, yet in the post they imagine that the taxi symbol would be created in a similar manner as the run from radiation symbol.

** It is however certainly not perfect, I'm a bit concerned with how people accustomed to reading right to left would interpret the bottom, it could well mean "if you run you die". However the symbol was apparently tested in China, Saudi Arabia and Morocco, so at least due diligence seems to have been done in that regard.

January 03, 2007

A Question for 2007: When is inequality a good thing?

The internet was supposed to be the great equalizer, the tool that would let anyone become a publisher, a news source, a movie director or the creator of even new medias. Shockingly enough in large part it succeeded and the predictions came true. Anyone on the right side of certain economics and techno-literate thresholds can indeed go online and distribute their works for little or no cost. We live in a world of publishers now and it's great in many ways, for one it enables this blog to exist. Yet something also went horribly awry in the process. We got everything the internet promised, everything except the equality.

In a world of millions of news sources we still focus our attention on a select few. There has been a bit of a reshuffling at the top for sure, new information powerhouses have stepped up and dominated, while some of the old media players have stumbled while others danced nimbly into newly global audiences. But information continues to follow a power law curve, which roughly means we focus 80% of our energies upon what emits from just 20% of the providers, and the top 1% command half of our total attention. Wealth too follows this distribution, with the super rich dominating absurd amounts of the world's cash flow, and the payouts to the top dogs at the likes of Google, MySpace and YouTube only reinforce this inequity.

Equality is a concept wrought with it's own inequities. We pay incredible lip service to it as a concept, but rarely implement it well in reality. There are only a few people willing to defend say the extreme difference in earnings between top Wall Street executives and the entire quarter of New York City's population that lives below the poverty level while also living in one of the world's most expensive cities. But there are few still who are actually willing to do something about it.

One of the ironies of inequality is that it's almost always looked at a bad thing, when in fact it often is exactly the opposite. Take your blood for example. You may have left small drops from cuts and scratches around your childhood haunts. You've probably given a few samples that now sit in testing labs or medical disposal sites. You might have donated a few pints that now sit in blood banks or circulate in some form through another persons body. But the vast majority of your blood stays within your body and you wouldn't want it any other way, would you? Your blood evenly distributed across the globe wouldn't do anyone much good, would it? That globe of course is an inequality in itself, stars, planets and atmospheres are ultimately the result of a radically unequal distribution of elementary particles.

Equality of course can also be stunningly boring. We wouldn't want all flowers to be equal in shape and coloring, nor do we enjoy it when every building looks the same. But none of that takes away from the fact that the inequalities of power, wealth and culture we tend to focus on have awful and far reaching consequences. Consequences we don't often actually address. There is a danger in shifting more attention towards the overlooked space of positive inequalities, a risk of de-emphasising the existing problems even further than they are now. But with that risk comes the potential to find solutions. Perhaps, but just perhaps, the fact that so little is actually done to address the radical inequalities in America and beyond stems from that discord between the idea of inequality being bad and prevalence of subtle examples of where it isn't. More than that though is the prospect that somewhere within the examples of positive inequality lies an answer, or at least a start of answer to how we can transform the negative inequalities around us into a better state of being.

So it's 2007 now, maybe ask yourself, when is inequality a good thing?

December 31, 2006

The Long Tale of 2006

2006 is racing to a close and you may well be aware that Time Magazine has named "you" person of the year. If you work for a financial firm on Wall Street, in the City of London or on whatever expensive piece of real estate you've landed you probably could have figured that out by looking at your record breaking bonus check. Of course if you worked in New York's financial industry you were already making over $8,000 a week before that bonus even kicked in.

Across the East River from Wall Street there are parts of Brooklyn where the average household income per year is less than that average wall streeter is making each week. If you lived in one of those household you might be a bit more surprised about being named person of the year, no? Of course this radical inequality in income distribution isn't exactly news to anyone, it's been around ages and statically mapped out by the Italian economist Vilfedo Pareto about a century ago. If you graph that distribution out what you get is something called a power law curve. In 2006 though the trendy terminology was "the long tail", a phrase for just one part of the power law curve, the part where those of us making less than $8,000 a week happen to reside.

The long tail is in large part a phrase created and popularized by Wired Magazine's Chris Anderson in a book and blog of the same name. While I doubt Anderson intended it as such, the long tail is one of the more misleading pieces of rhetoric around. What Anderson wants to focus on is the stuff that drives Time magazine's "you", the increasing world of user generated content, movies, sound files, Flash animations, blog posts and all the other amusing detritus of unknown quality filling out the internet. And there is no denying that this stuff is exploding, sometimes in quite interesting ways. But what makes the long tail so disingenuous is that what happens in the long tail has almost no ramifications on what happens in the head. The language of the long tail often takes on the rhetoric of democracy or even revolution, but the fact is that nothing about the influx of user generated content necessarily impacts the inequalities encoded into the power law curve. If anything the long tail presupposes inequality, and Anderson is in essence saying "pay no mind to the inequalities at the top of the internet, look at all the exciting stuff over here in the tail".

Of course it's become increasingly apparent that the internet is wrought by, if not outright characterized by inequality. Web traffic is even more concentrated to the largest web sites.* Of course a couple of those top 10 sites are actually places like YouTube and MySpace where large amounts of user generated content drives traffic and then deposits money in hands not of the creators, but instead in the coffers of the large corporate landlords. Nicholas Carr aptly compares this setup to sharecropping. One can see foreshadowing of this effect in Chris Anderson's writing, for all his hyping of the long tail he sees far more concerned with creating the structures and situations in which long tails can occur than he is concerned with what things might actually be like inside those long tails. The owners of the MySpaces and Flickrs and the producers of video editing softwares are getting rich by enabling an unprecedented amount of people to make and distribute their own 'content'. And way off at the edge of these systems are a few alpha users who also may be getting rich, or at least famous to their peers by making some of that content. They aren't in the long tail though, they are in privileged head. Those in the tail might have a little fun, but they get neither the audience nor financial rewards that demarcate success in this 21st century culture.

No matter how you spin the long tail, and without a doubt there are aspects of it that are interesting and perhaps even admirable, you can't detach the long tail from the power law curve that it is part of. And as long as we are talking about a power law curve, we are talking about radical inequality. Unfortunately that's something that's predated 2006 for quite some time and doesn't look to be leaving with the new year either...

- If you follow that link though, you might notice the story has a rather misleading headline "The Shrinking Long Tail - Top 10 Web Domains Increasing in Reach". That the top ten domains are increasing in reach is a fact, at least if the statistics in that article are correct, but that fact has no correlation the long tail shrinking or rising in any manner. It's perhaps easier to think about it in terms of income. When the rich get richer, does that mean there are less poor people or more? That's just not a question that can be answered without more information. The top websites are getting richer for sure, both in terms of money and in terms of attention paid to them, but there may well be millions of new tiny sites stretching the tail out further and further.

December 30, 2006

Scarcely Economics

The cliche goes that the flapping of a butterfly wing in Asia just might be the movement of air of that triggers a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. The math of that cliche is relatively developed, but it's mainly a computer simulation situation, actually showing the effect of those flaps is a beyond our sensors...

Somewhere on the edge of academia circulates the idea that economics is defined as the "study of how human beings allocate scarce resources". It's a definition that doesn't show up in most dictionaries, but it has a stubborn persistence. Scarce resources are of course an important component to economics, but is it really all there is? Most definitions instead fall rather close to Webster's: "a social science concerned chiefly with description and analysis of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services."

It's a curious distortion to make economics strictly a study of scarcity, and like the textbook chaos theory case it starts out as a rather minor disruption. Scarcity is after all essential to the generation of price and value, and economists hold those processes dear to their hearts. There is of course more to economics than just studying scarcity, but it's not exactly an alien concept. What's curious is what happens when non economists start latching onto the distortion, what's curious is when scarcity meets attention from three different directions.

Michael Goldhaber, Richard Lanham and Georg Franck, all more or less independently converged on a phrase, "the economics of attention" in the past decade or so. At the core of their thought (which varies widely in quality) is the observation that in a time where information is becoming, in Goldhaber's terms, "superabundant" what is scarce is attention. It's an interesting observation, one well worthy of economic exploration, but oddly enough Goldhaber, Lanham, and, from what I can tell without reading German, Franck as well all want to go much further. They pull back and wheel up with their distorted version of economics as being solely the study of scarce resources. It's a funny equation, an interesting observation plus a distorted definition equals a call for a whole new construction of economics.

The first irony is that if economics was really just to be about the distribution of scarce resources it wouldn't even be about money. For money is about as far from a scarce resource as there is. It can be printed out by any government and by a skilled counterfeiter too. Or it can be generated by any group or organization with enough clout. Airlines for instance have essentially created their own currencies of frequent flier miles, while towns like Ithaca, New York have created their own regional currencies with little more than a printing press and a PR campaign. Of course in this digital age a printing press is way to heavy, banks of course can famously create money by lending out money that people deposit for savings and in the twenty first century this operation has been extended into financial maneuvers of baroque complexity that span the globe in seconds. Money is anything but scarce. The problem is not there is not enough, but that it circulates with a damaging inequality.

Goldhaber and Lanham though don't seem really want economics to be about money anyways though. They'd much rather refocus it all around attention. It's an act of overstatement that probably does them far more harm than good. They get to make exaggerated statements about the need for a new economics, perhaps it makes their observations seem bigger, but it also makes it far easier to ignore them. They might want it all to be about attention, but quality and accuracy still have a bit of value left in them. Someone is going to make a career pulling attention scarcity into the wider economic stream of thought, but it just wont have the extreme ramifications the attention lovers vest into it. Goldhaber's work in particular is still worth of future attention, but until he pays a bit more attention to what economics actually is his insights will probably remain obscure to the discipline...

November 11, 2006

Irreversibly Google

The story of Google is in many ways the archetypal engineer's dream. They invented a better way search the web, set up in a garage-like space and rose to the top. But engineer's also value results that can be reproduced, and part of what makes Google so scary is that it can not be reproduced. As hard as Yahoo and Microsoft are trying, with obscene amounts of financial, engineering and computing resources at their disposal they can't generate search results as good as Google's. The search world is already oligarchical, but as google rapidly turns into a verb, it is well on it's way to become a monopolized space.

Page Rank you see is an irreversible and an irreproducible process. Page Rank is the name for the key aspect of Google's search algorithm, the engineering breakthrough that make Google so much better than all those now dead or battered search engines of the 1990's. And it's also the thing that makes it so damn hard, if not impossible to make a search engine as good as Google's. You can reverse engineer Page Rank of course and you can be damn sure both Yahoo and Microsoft have invested plenty of time to that effort. The problem though is that Page Rank just would not work if you ran it today, and that's why Yahoo and Microsoft just can't provide the same quality of results as Google.

At it's core it's a problem of the data set. Page Rank's big break through was that it realized that links between webpages could be used as a way to judge the quality of a piece of content. If a page was linked to by multiple sites odds are it was a better page than one with no incoming links. Furthermore if the links came from other high quality pages the odds would be even higher. I wrote that all in the past tense though, because Page Rank is a victim of it's own success. The internet is now filled with massive amounts of pages generated with the explicit goal of hacking Google, of pushing sites up higher in it's search results. The internet as a dataset is now dirty, if not filthy.

This is a problem for Google of course, but it's not nearly the same problem it is for them as it is for it's competitors. Google needs to deal with the many sites trying to hack it's results, but it has a major tool to fight them, the data generated by Page Rank before search engine optimization became a profitable and fulfilling career. It means Google weighs slightly towards older sites, ones established in the era of clean Page Rank, but it also means that anyone trying to reproduce Page Rank by spidering the internet today, just can not get results nearly as good as Google's. So until someone devises a brand new algorithm, it's going to be Google's internet and the rest of us are just searching for our own small little piece of it...

November 01, 2006

Pro-markets, Anti-profits

Pro-Markets, Anti-Profits

It's a statement so dangerously wrought with oversimplification that I've been avoiding saying it for a while now. But simplification can sometimes be as, or more, useful than oversimplification is dangerous, and nothing sums up my political economic stance better than reducing it to two positions: pro-markets, and anti-profits.

First and foremost this stance requires a split from a great mistake made by most traditional appwroaches to economics from critical marxism to laissez faire boosterism. Market activity and profits are not the same thing, but in fact too very separate forces and while they can and often do work in concert with each other, they do not always do so and certainly do not need to. If the goal of economics is to gain an understanding of how economies operate in order to improve them, and I believe that that has to be a major goal of economics, than coming to grips with this split is absolutely essential.

My stance may simplify down to "pro-markets", but it is essential that this stance not be confused with the far more common "pro-market" approach. The difference might on the screen or page be a matter of one letter, the addition or absence of an "s", but like many differences between the singular and plural this is actually a difference of nearly infinite ramifications. There are many (upon many) markets in this world, but "The Market" in the sense it is often used does not exist at all. Of course "the market" can exist in a very local sense, the way a mom might tell a kid to "go to the market and pick up a quart of milk." But "The Market" in the abstract sense that both proponents of "The 'Free' Market" and their many critics like to use it just does not exist at all. There are many markets in this world and the behavior of these markets in fact varies wildly. The baazar in Marakesh just does not function the same way the London Stock Exchange functions or the the way my local coffee shop functions. Heck, even the New York Stock Exchange functions differently than the NASDAQ market, and in fact there are even multiple markets for New York Stock Exchange stocks, each of which behaves slightly differently. The market for art at Sotheby's auction house is different than the market for art in a Chelsea gallery, which is different than the market in an Amsterdam gallery which in turn functions radically different than the nearby Dutch flower auctions.

A market is at it's core simply a place of exchange, a bounded area where people converge, either physically or via a mediating technology, in order to move exchange goods, services and information. To be pro-markets is to be in favor of the existence of markets, and to understand that each and every one of them behaves differently. Sometimes this behavior can have quite positive results, sometimes they can be rather negative and generally what reality gives us is a complex and nuanced mix of the two. Overall though markets are places of exchange and exchange itself is a healthy operation. By realizing that some markets behavior better than others we can begin the process of designing better markets, emphasizing those that work well and improving those that need work.

In order to evolve and create better markets, we need to make at least one key conceptual leap, me must break the historic tie between market functions and profit. Markets do not need profits in order to function at all. In fact it's possible to interpret profits in such a way that they are actually indications of an improperly functioning market, where the existence of profits indicates an inefficiency in market actions, a flaw that a more perfect market would correct. It's not an approach I'm about to follow, because perfect markets do not exist in the real world, and what I'm interested in is working markets, and the task of making them actually better.

Profit is perhaps one of the more unclear and misunderstood words in the english language. So much so that a large portion of the entire profession of accounting is dedicated to the art of obfuscating profits, pushing and shifting them around in ways that tend to be highly unprofitable to the public at large but rather rewarding to a select group of individuals. And just as profits can miraculously transform in the hands of a skilled CPA, the very meaning of the word has evolved in a rather confusing mash of economic theory and government action.

In classical economic theory, profit was deeply associated with the figure of the entrepreneur. Profit was how these idealized people would make their way in the world, they would purchase goods, transform or move them and then resell in a market. The difference between their expenses and the selling point, provided it was positive, was profit and this profit functioned as the entrepreneur's reward, salary and means to continue their business. It's quite a positive viewpoint of profit, and unfortunately it has little to do with the reality of how business is conducted and profits actually calculated today.

The entrepreneur as mythologized by classical economics barely exists anymore. Even those bold individuals who embrace the title today tend to wrap their enterprises in the protective skin of some form of limited liability corporation rather than proceed as sole proprietors or in traditional partnerships. Profits that pass through these organizations take on a radically different form than they do in the naive view of an entrepreneur. In fact even in a sole proprietorship or partnership profit transforms the minute that salary is introduced to the equation. For salary is after all an expense and profit is from a legal standpoint what occurs after all the expenses are paid. As soon as an entrepreneur is getting a salary, suddenly profit is no longer their just compensation for effort and risk, but in fact what is left over after they have been compensated for their time and work. Some of this profit is reinvested back into the enterprise of course, but all to often it is extracted from the system and into the hands of a limited set of individuals.

Classical economics is essentially about "individual profit", yet in this day and age while there are plenty of individuals making profits, it is almost always "organization profit" that they are making. Organization profit is not the organization's reward for good work, but in fact it's punishment, this is money that is extracted from the organization and back into private hands. It is still entirely possible to incorporate and run a business as a not-for-profit corporation, and that's an action with rather interesting ramifications. Such a business would not be eligible for federal tax exempt status in the United States, and it still could generate surplus revenues for which it would need to pay taxes, but those surplus revenues would not actually be profits. These revenues would have nowhere to go but back into the not-for-profit corporation. This is the corporate for as a (semi)closed loop system. There is still plenty of money going in and out as expenses and revenue of course, but ultimately the money flowing through the system must remain concentrated on the organizations goals and purposes. For profit corporations are not closed at all, but in fact function as the opposite, they are designed explicitly to function as money extraction machines concentrating wealth into the hands of a few individuals.

A certain type of reader might be tempted to look this view of profits as something akin to Marx's "surplus value", but nothing could be further from the truth. Marx's construction hinges upon a rather absurd and mythical idea of labor value, and ultimately views all surplus revenues as a negative. I however take the exact opposite stance, that surplus revenue is an incredibly positive thing, it is ultimately a key engine of economic growth. It is only when surplus revenue is transformed into "profit" and then extracted from the organizations that created that a real problem emerges. So while marxists like to see the economic problems of the world as being a function of "the market", I locate those problems in a very different place, in the hands of the individuals that skim off the top of market activity, and in the organizational forms that enable and encourage this behavior. This leads us to the second challenge of a pro-markets and anti-profits stance, how do we develop better organizational forms for economic activities?

The for-profit corporation in it's current form is less than 200 years old. It is only in the last century that it has truly erupted to become the dominant economic form in Western economies. There is no reason other than historical circumstance that it needs to be the dominant form now. In fact from the Korean chaebols to the Basque Mondragon Cooperatives there is plenty of evidence that other organizational forms can function on a global industrial level. In The Wealth of Networks Yochai Benkler has argued that the networked efforts of open source programers and wikipedia addicts represents a whole other economic organizational form. But ultimately I believe that's just the beginning. Organizations and markets are two forms of entities that exist on a scale larger than the individual. It makes them exceedingly hard to conceptualize, understand and transform, but they are ultimately the creations of humans and it is well within our means to improve upon them. Pro-markets and anti-profits, it is an over simplification for sure, but that is where I start.

October 10, 2006

Economics/Attention

It's the year 2006, how do you get away with publishing a book without ever googling your title? I have no idea but Richard Lanham's new book The Economics of Attention curiously has no references at all to Michael Goldhaber's The Attention Economy: The Natural Economy of the Net, hmmmm. Goldhaber's work was published online in a peer-reviewed journal nine years ago. It's core premise is practically identical to Lanham's. Google the title of Lanham's book and Goldhaber shows up as the third full result, behind only references to Lanham's book. I'm all of nine pages into that book so who knows how it stacks up, but it sure hasn't started out right, at least if your a nerd like me who reads the bibliography first...

October 09, 2006

"Corporate Social Responsibility" and the "Bottom of the Pyramid"

Can a corporation have a conscience? Nobody really asked that at Columbia Business School's Social Enterprise Conference 2006, but the question underlaid it all uneasily. Well, at least for me. The fact that the conference exists at all clearly indicates that plenty of business school students have some conscience, but they fact that they are in business school in the first place also clearly indicates that conscience is modulated by a certain faith in enterprise.

The buzzword that resonated loudest to me in this buzzword filled environment was "corporate social responsibility" or CSR for short. The idea is that companies need to healthy citizens or something, but in practice it seemed more like a way for people embedded deep in giants like Citicorp or Alcoa to soothe their own consciences with a small diversion from the corporate cash flows. Strikingly absent from the discussion was any sense of how CSR spending, when it exists at all, might stack up against the rest of these giant's budgets.

Jim Sinegal, the CEO of Costco, at least talked real numbers as he accepted an award of some sort. He proudly threw up a quote about how it was better to be a Costco employee or customer than a shareholder. The Costco philosophy is to cut costs everywhere except when it comes to employees, who if I remember his sliders correctly represent 70% of the companies operating cost! But even as he deflected personal credit away from him and out towards his entire management team it was quite clear this approach is merely an iteration of the age old concept of the enlightened dictator. The employees/serfs may be happy, but only because the situation is enforced from the top. Like his counterparts at the head of Starbucks and American Apparel, Sinegal has no structure in place to ensure that his enlightened approach can be anything other than a management decision.

This situation has deep roots in the history of management theory, it's something of a Taylorism versus Fordism approach. Happy employees is clearly a successful business style, but so is the far more exploitative bean counting tight ship way of management. Costco might be better for employees than Wal-Mart, but both still are out there and both perpetuate hierarchies that pump money into a small upper class. Some kings were better to their serfs than others, but either approach meant the existence of a kingdom. And I don't think it's a coincidence that the corporate organizational form emerged just as democracy began to unstabilize the aristocracies of old.

It's not the aristocratic side of this corporate finishing school that's really disturbing though, it's the religious one. Most people in these environs have some sense, however watered down, of their privilege and the larger inequalities out there. It's the people who truly have a faith in "The Market" that really freak me out. The ones that really believe that "CSR" will spread because consumers demand it or scarier still those that believe in BOP. BOP stands for the "bottom (or sometimes "base") of the pyramid", the billion strong poorest of the poor. The idea is that by turning these people into entrepreneurs partnered with multi-national corporations and selling to their equally poor peers poverty can be eradicated.

One of the key mantras of BOP believers is that it can not be reduced to just selling goods to poor people, but instead requires a far more intense and interlocking relationship with the target market. This is absolutely true. What BOP is about is not selling products, that's just a corollary to all. What it is about is selling an ideology. Like the centuries of missionaries before them the BOP proponents think they are saving when actually they are converting.

Poverty is an issue with far more ramifications than can be explored here, but the simple point is that not having a lot of money can only be seen as an absolute bad thing if you follow a faith that revolves around the accumulation of wealth. Certainly there are probably problems that we as westerners see in the populations at the "base of the pyramid" that the people themselves might also agree are problems. But there are also problems that are far less physical and far more religious in nature. Like the heathens of old these are people with different value systems than us, and like missionaries trying to save souls, it's quite likely some of the problems the BOP practitioners are out trying to solve are only problems of faith. And as well meaning as they may be I for one have no faith their little enterprise...

October 08, 2006

Random Question

Why is it that anytime you read about the advertising or video game industry, both of which are massive profitable and pretty much icons of our culture, they always claim to be struggling? Are industries based upon rapid fire information inherantly less stable than ones based on selling material goods?

October 02, 2006

The Ghost Map

When Steven Johnson says his next book is going to be about cholera, you can't help but be a little surprised. Yet while it has very little to do with Johnson's recent books on video games, television and brain machines, The Ghost Map is much less a departure and much more of a welcom return to the territory of his first two books. Follow the paths set by Interface Culture and Emergence till the point where they converge and you will find The Ghost Map. It's easily Johnson's best work yet and perhaps the first classic urbanist text of the new century.

The setting is precise, a handful of blocks in London's Soho neighborhood, late summer 1854. The stakes however are impossibly large, with London at the lead, the world in 1854 is getting increasingly urban, and the more urban it gets the greater the threat of cholera becomes. Cholera's vector of transmission is the digestive tract. It comes into the body through drinking water, and exits the other end, taking with it an extraordinary amount of a person's internal fluids, and usually their life with it. This leaves the cholera bacteria with a rather nasty biological challenge, it's main point of reproduction is the small intestine, yet getting from one person's small intestine to another is quite a journey. For most of history this meant cholera played quite a minor character.

As the industrial revolution pushed more and more of the world into cities, a unique opportunity for cholera arrived. When hundreds of thousands, or even millions of people squeeze into the tight streets of a city, their shit tends to flow downhill, and often straight into the same river that their drinking water is pulled from. The city literally began to function as a shit eating, or more accurately drinking, machine and cholera epidemics began to pop up regularly. The result was often tens of thousands of deaths in short periods of time. If the urban form was going to continue to grow, and all the pressures of the industrial age were pushing in that direction, it would need to deal with the problem of cholera. In London, in Soho, late summer of 1854 in a remarkable series of events the city essentially learned how to deal with cholera and this is the story of The Ghost Map.

Johnson approach to history clearly owes a certain debt to Manuel DeLanda's A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History but this book is almost it's inverse, centering on a highly specific point in time and space, and following a potent narrative. Perhaps you can call it "A Thousand Hours of Linear History". Those compact hours that form the core of the book are in a way an intricate tracing of something straight out of DeLanda's work, the crossing of a material threshold which then allows humans to settle into entirely new urban formations. For only by conquering, or at least learning to manage, cholera can people and cities evolve towards the massive scales we see today. DeLanda however labors hard to produce almost entirely material histories, invoking odd concepts like robot historians and the viewpoint of minerals themselves. Johnson follows something of this form when he talks about bacteria and cities, but then interjects two intensely human actors into the picture to produce a radically different sort of book.

The most striking academic parallel to The Ghost Map is not DeLanda's work at all but Bruno Latour's The Pasteurization of France. It's been a long time time since I cracked upon that tome, and honestly I'm not certain I ever finished it, but Latour is telling a strikingly similar tale to Johnson, tracing the complex interplay of factors that lead Louis Pasteur to his ideas and the world into adopting him. Latour of course is almost deliberately obtuse in his explorations, his goal at the time was to multiply the possible explanations, so once again Johnson again takes a somewhat inverted approach. Johnson is of course one of the clearest and must lucid of the current crop of science and technology writers. Given Latour's recent exhalation of the art of writing as core to the successful application of his Actor Network Theory, one has to wonder if Johnson may have inadvertently produced one of ANTs finest documents.

Like Latour Johnson breaks from the hero model of scientific discovery. But while Latour and his ANT practicing colleagues attempt to introduce as many actors, both human and non-human, into the story as possible, Johnson finds a much more coherent middle ground. The traditional telling of this story focuses around John Snow the lone scientist fighting against prevailing opinion, and Johnson does not try to discredit him, but instead adds three more actors to the stage, the microscopic cholera bacterium, the massive water infrastructure of London itself, and the very human and very social figure of Reverend Henry Whitehead. The result is a complex yet compellingly clear tale of social, scientific, organic and urban forces interweaving to produce both a tragic outbreak of disease and ultimately it's solution. It may well be the best book on urbanism since City of Quartz, yet way more optimistic, and well worthy of a space next to Jacobs on your urbanism shelf.

September 27, 2006

Saving Through Destruction

BLDGBLOG: City of the Pharaoh At the end of this pretty incredible post (not an unusual thing at BLDGBLOG) is mention of an archeological discovery from back in 1850. But by digging stuff up in 1850 was evidence we could use here in 2006 destroyed? Is our current archeological practice, so intent on discovering the secret past, actually destroying it as much as it is discovering it?

September 15, 2006

It's Only Value Is That It Has No Value

All my bicycles are street bicycles, there are no dirt trails, half pipes or beautiful mountain passes in their future, only the torn urban asphalt of New York City. But there a whole variety of urban bicycles out there, and my latest frame finally emerged from six months of bike shop limbo with a working bottom bracket, which gives me three bikes, or one too many for an apartment dweller like me. The only question is which bike to get rid of, and it's proving to be a trickier problem than expected.

From a purely bike riding perspective its an easy question, the one I call my neighborhood cruiser has practically no value at all, it's worth more as parts than as a complete bicycle and those parts are not worth much.** It shouldn't be too hard to part with, should it? But that is exactly the problem. I live in New York City and this bike is actually tremendously valuable based on the sole fact that it has no value.

This is a bike I can lock up on the street and not stress about in the least. I can, and do even leave it out overnight. From an economic standpoint this creates quite an interesting situation, a value that can not be monetized, for the very act of this feature taking on a monetary value would eliminate any value that existed. A bike with a real monetary value is worth stealing and that translates directly into both financial risk and psychological stress for a bike owner.

From a purely urban perspective this is an easy problem as well, the nicest bike, with the nicest parts has the least use in the city. Sure it's nimble and quick, and the Phil Wood hubs are both buttery smooth and the most capable of handling the urban grit and grime over a lifetime that via sale or theft will probably be far longer than I will own them. It's both a little to valuable and little too sensitive to be an everyday, no matter the weather, vehicle. It's tight track geometry can zig and zag through every urban obstacle, but it also translates every bump and crack in the road back to the rider with far more precision than comfort. It is quite literally a physical manifestation of the phrase "too much information". As beautiful as thing is to ride it tells me a bit more about the state of the streets beneath me than my body wants to know. But as much as I love the city this is far to sweet a machine for me to just let go of and so it stays, it's visceral aesthetics trumping pure practicality.

Tactically the best maneuver would to take the middle machine, and somehow make it "street stable", somehow degrade it's value to a point it can be left locked up along overnight without much stress. It's perhaps an impossible task, how do you devalue a bicycle without eliminating just what makes it a good, fun thing to ride? This is a frame that's been evolving into what might be called an "inverse hybrid", a new style monster uniquely suited for urban riding.

The bicycle industry currently pumps out some hideous beasts it calls hybrids, essentially overgrown mountain bikes designed to be ridden fully upright. Basically they make it easier to ride over potholes while sucking the joy out of every other aspect of urban bike riding. The inverse hybrid is the reverse, fixed gear gives you control and real sense of the road, while chopped riser handlebars put you in the ultimate urban riding position. Higher than the drop bars of a road bike, but lower and narrower than the chunky riser bars of a mountain bike. It handles almost like an overgrown BMX, if a BMX was capable of any real speed and efficiency on the city streets. It's a stance that gives a unique combination of maneuverability, visibility, hopping ability and just the right feel of the road in your hands.

The challenge now is to make an inverse hybrid that no one wants to steal. So just how do you make something that's only value is that it has no real value?

** This is particularly true at this time of year, the beginning of the fall and the end of the bike season. Odds are for a few months in the spring this bike will be more valuable than the sum of it's parts, only to lose that property as days begin to get shorter.

September 09, 2006

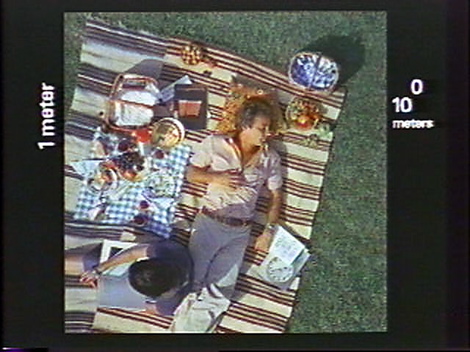

Lunch Design/Conference Design

Actually breakfasts are always worse, but I forgot to photograph it. One thing conference designers never seem to think of is what food is best for creating a great environment. Lunch was a sandwich, which is mainly carbohydrates, with a bit of veggies and a modest amount of protein. There was also potato salad (more carbs), a banana (more carbs) and a cookie (more carbs). That's a formula for a food coma. The talk or two after lunch are never the most fun are they?

Breakfast as I said is worse. Pastries and muffins, all carbs, no protein, another recipe for putting people to sleep. In America this diet gets counterbalanced in part because people have plenty of energy after sleeping all night and in part because it's offset with large amounts of low quality caffeine. Downers cut with uppers, not exactly the path towards a healthy day, nor necessarily for the best conference experience. It works for the most part, minus that hour of post lunch coma, but can it be designed better?

September 06, 2006

Social Hardware

Somewhere off on the periphery of my online home there is a whole conversation brewing about the merits of "social software". The spark for this round apparently is someone named Ryan Carson and his blog post on why he doesn't use social software. Now this is the sort of conversation I try and filter out and ignore. It was sort of pitiful from the start, a blog post is a piece of social software, so using it to proclaim you don't use social software is pretty much a nonstarter. Then there was Carson argument, which is essentially "I'm too busy, plus I'm married now", or in other words he's too lame and important to be interesting...

Now somehow Carson elicited a ton of response from some rather smart people, although Fred Stutzman's is probably the one most worth linking too. What was interesting to me though from these response was not what was said, although some was certainly insightful, but what was not. There was plenty said about social software but nothing at all about social hardware.

Now it's easy to say you don't have time for social software, although if you have time for email then clearly you are lying, as email is social software in it's purest form. More than that, do you have time go into conference rooms for meetings? Do you have time for drinks after work with colleagues and clients? Do you have time to attend conventions for work? Do you have time to meet friends for coffee, or go to a concert or ballgame or maybe head to a museum? Or if you are a married man like Carson, do you have time to go to a restaurant with your wife? A conference room, a convention center, a bar, a coffee shop, a stadium, an art gallery, these are all pieces of social hardware. Large objects constructed to allow you to interact with other people in a wide variety of styles. If you have time to be social you have time to use social software. Maybe you prefer other forms of socializing, but that is a choice you make. Everyone has time to be social, so to argue that social software is in trouble because it takes too much time is absurd.

A computer by itself, is a piece of antisocial hardware. It is all about a person alone in from of a glowing, captivating screen. But once that computer is connected to a network it has potential to become a social tool, but only if unlocked by software. This software can come in any flavor, look and feel capable of being generated by a Turing machine. And making new flavors and fads is pretty cheap, certainly a lot cheaper than creating a new bar, restaurant or convention center. Yet while what can go on the screen may be infinite, the social aspect of it all remains deeply tied to the hardware, making the machine social is simply the act of linking various nodes of a network together.

Social software is the art of managing links on a network over time. Instant messaging is a temporary and private link in real time. Email is temporary and private but time shifted. A blog post is also time shifted, but is public and if not permanent than at least has a much longer half life than a typical email. The classic social network apps like MySpace, Friendster and Facebook are different. Instead of turning links on and off when needed, they establish links once and then make them essentially permanent. What happens next is just a series of other social software styles overlaid onto this network. Most of the fuctionality of these sites is as blasé as it gets, replacements for email, blogs, photo albumns and bulletin boards, usually in a somewhat inferior form to the more deadicated versions of those apps. What makes them unique is merely that you can now use your social network itself as a modulating factor. It's a classic case of constraint unlocking potential. By constraining functionality to just a space determined by the semi-permanent links of a person's social network, these sites can channel other existing pieces of social software into a more vibrant, and from the looks of the use numbers, addictive form.

It's not quite a "nothing new under the sun" thing, there is a new twist to the new social softwares, but there is not that much new. To say that you don't have time for social software is essentially the same thing as saying you don't have time to be social at all. Maybe you prefer more of a hardware setting, to socialize at a country club or dive bar or at church or at ballfield. Maybe that leaves you too drained to keep up with your Facebook feeds. But it's not because you don't have time for social software, it's because you've made a simple choice to pursue a different social avenue. One that presents a different set of nuances and twists then what is available online. That's your choice and perhaps it's a great one. But social software is no more time consuming than any other social structure and it will continue to evolve in interesting directions. Now keeping up with those directions might indeed be tiring, but only if you are conscious of it. The people who actually are using these things without thinking about it are the ones truly pushing the form, to them their community lies in part in software, and from here on in, that is pretty much something to take for granted.

August 31, 2006

A Question of Scale

I keep on trying to write a post on how difficult it is to write about difficult it is to write and talk about scale. I keep of failing cause, well it's really difficult to write and talk about issues of scale... So instead of trying to say anything meaningful I'm just going to ask for advice. What works can you recommend that deal meaningfully with the concept of scale? Works that address how we as humans can talk about phenomena that occur at scales of time and space that differ from our standard 5-6 feet above the ground and cycles of seconds and hours, days and months?

What I'm really interested in is the physical and conceptual tools that we use to do this work. Things like microscopes and the periodic table let us deal meaningfully with objects and actions that occur on small scales far out of sight of our naked eyes. But it strikes me that the tools to deal with scales slightly larger than human are severely lacking compared to both the ones we use to address the microscopic and grand reaches of outer space. But than again maybe I just haven't been exposed to the right tools.

August 28, 2006

Imaginary Feedback

What happens when you press a button? A button can trigger close to anything nowadays, but it's not what the button triggers that I'm interested in at the moment. Until our current age of screens a button pretty much by definition produced a bit of tactical feedback. You press a button and it presses back at you, giving you a confirmation that yes indeed that button was pressed.

Even in the screen age, most buttons still produce tactical feedback of some sort. Every letter of this text I type comes complete with a nice, Apple designed, bit of feedback, each button of the keyboard press gently back at me. The buttons on the screen are trickier, the tactical feedback tends to still exist, but slightly abstracted, you press the mouse, or trackpad or whatever button, and you feel a small kickback, albeit one a handful of inches away from the button you are actually looking at and in your mind clicking upon. On screen buttons tend to compensate for this distant tactical feedback by adding visual and or audio feedback to the mix.

When it comes to touch screens though all of sudden the tactical feedback it gone completely, all that is left is whatever audio or visual guides the designers have left in the system. It's for exactly that reason I dislike touch screens, despite their name they just don't feel right. When I use a Citibank ATM, which is often as they are my bank, I tend to tap the screen not with my finger, but with the side of my ATM card, there is something completely wrong about "pressing" a hard glass screen, that neither gives in nor gives back any feedback as you push upon it. Its a cold and unresponsive feeling, a dead interface into a live machine.

Of course for all my dislike of the touchscreen I've been a big Treo fan since the days it was a clamshell. Maybe it's the softer screen, or the fact that you don't usually need to use the touchscreen if you don't want to, or maybe it's just the superiority of the Palm interface design. I still prefer real buttons and the Treo has no shortage of those with a full QWERTY keyboard, but it also showed that a touchscreen could work maybe. Until it stops working of course, which my current Treo's has been doing intermittently the past couple days. The Treo is well designed enough that this is just a minor annoyance, so far it's always started working before I've gotten fed up enough to call up insurance for a replacement. But it also led to an interesting observation. When the touchscreen is not working it literally feels different, harder, as if a secret mild tactical feedback mechanism just disappeared.

Odds are this is a psychological phenomena. I touch the screen and because I get no visual or audio feedback somehow my brain feels the screen differently. Yet every time the touchscreen cuts out it feels distinctly like I can feel the hardness of screen before my eyes register the failure of the touch to work. Its as if the eyes-fingers-consciousness circuit is faster than the simple eyes-consciousness one. Either way, when the touchscreen is working it seems like somewhere in my mind, the act of touching a handheld screen and seeing visual feedback of a button press is creating some sort of phantom tactile feedback. A subtle but real impression that screen is softer, has more give, than it really does. Does that mean there is hope for full touch screen interfaces? If the long circulating rumors about Apple's new video iPods are true, it sounds like Steve Jobs is better there is. Me, I'm not so sure, I still like to press real buttons.

August 23, 2006

Another Time

Every once and a while you catch a moment that makes you precisely aware of the sort of things you take for granted. I cherish those moments, it's rare opportunity to actually be able to see yourself in a bit of perspective.

I had one today after placing an order for a small sample quantity of items from a large industrial company. Their New York rep sent an email saying they'd mail me an invoice, and being a sample I would need to prepay before shipment. Somehow that bewildered me, I knew I needed to prepay, but I was ready to swipe my debit card that instant, or at least send the numbers over. It just seemed so slow, so out of touch with the rhythms of my day to day. Especially since I pickup my mail maybe twice a month. I've been spending years trying to eliminate mail, now my whole project is on hold till the US Postal Service comes through? How slow, how primitive! And all that was before I realized the invoice wasn't even getting mailed from here in NY, on reread it seemed like it was getting mailed from Switzerland...

Of course the real primitive here is me. I've been living too much of my life on internet time, instant gratification time, always on, high speed download time... If I want to get into the business of physical goods I need to learn the rhythms and pacings that make them work. One step at a time was the mantra when I finally learned how to make physical computing projects work, and that is probably how I'll need to address the issues of manufacturing real goods, things with real weight, things that move on the backs of trucks and across oceans in twenty-foot equivalent units. Maybe it will be frustrating, maybe it will be a welcome pace, either way I'll need change my perception of time, my culture of time, just a little to make it work.

August 18, 2006

The Value of Metcalfe's Law

For whatever reason Metcalfe's Law has been all popping up everywhere I look over the past 24 hours.

The July issue of IEEE Spectrum has an article "Metcalfe's Law is Wrong" that is probably the crystal under which all this attention can be formed.

Metcalfe's law basically states that a value of a network grows exponentially with the number of nodes. A telephone network with only one phone is worthless. One with two is usefully only to the few people who can reach those two phones. But a phone network with a million phones has a massive value. The authors of the IEEE article don't dispute the existence of "network effects", the fact that as nodes increase networks rapidly increase in potential value. What they dispute is the exponential math that Metcalfe, the inventor of Ethernet and founder of 3Com, uses. The authors instead argue for logarithmic growth, or something close to it. They are probably right.

They also make an important point that "Metcalfe's law" is not a law at all, but merely a empirical observation that serves as a useful guide for analysis. What they completely miss is the wide open flaw in Metcalfe's Law, which can be summed up in one word, value.

What the fuck does it mean when you say the value of a network increases, with the number of nodes? Well it depends on what sort of value you are talking about. A network of phones in a world of deaf people has no value no matter how many nodes it has. What a network gains when it adds nodes is not value but potential value. That potential value only can turn into "real" value when valuable content flows through the network from node to node. You just can't sit down with Metcalfe's law, in either the original exponential or new logarithmic version, and use it to calculate the value of your network based on the number of nodes. All those nodes are worthless if they don't have anything to say to each other.

You can build a network, you can get a guideline of it's potential value, but to unlock it you first need to figure out just what value you are talking about. And then you need to get that value into the network in a way that is communicable and then and only then will the network actually begin to produce the values you want.

update: not 10 minutes after I posted this I stumbled on Metcalfe himself responding to the IEEE article in quite an interesting manner. And as usual Fred Stutzman has some interesting things to say as well.

August 15, 2006

The Innocence of Power Laws

I've been reading a short book - an essay, really - by John Kenneth Galbraith called The Economics of Innocent Fraud. It's his last work, written while he was in his nineties, not long before he died. In it, he explains how we, as a society, have come to use the term "market economy" in place of the term "capitalism." The new term is a kinder and gentler one, with its implication that economic power lies with consumers rather than with the owners of capital or with the managers who have taken over the work of the owners. It's a fine example, says Galbraith, of innocent fraud.

- Nicholas Carr Rough Type: The Great Unread

I've long argued that the "natural" shape of most markets is a powerlaw, and that any deviation from that shape is due to some bottleneck in distribution. Get rid of the bottleneck and you can tap the latent demand in the market, unlocking the potential of the Long Tail.

- Chris Anderson The Long Tail: A billion dollar question