November 13, 2008

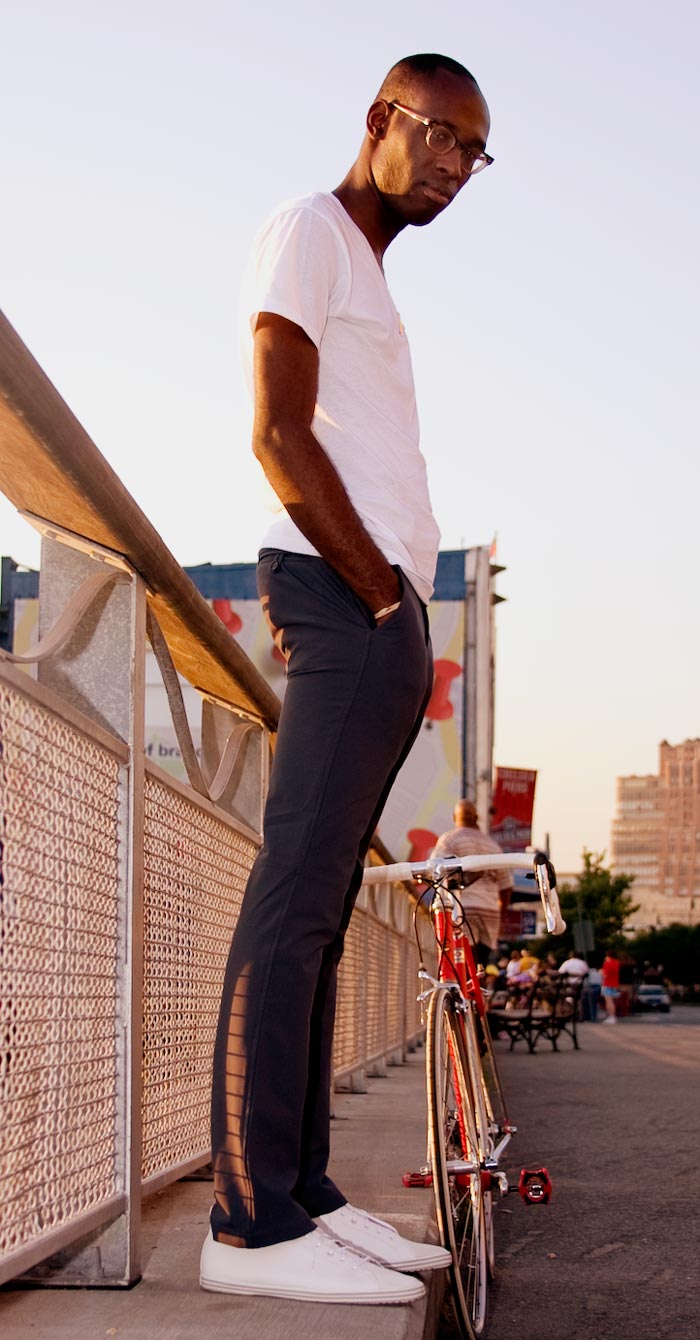

Outlier Tailored Performance

Outlier is my new venture. Probably find me writing a bit more there then here for a while. Outlier makes tailored performance clothing for cycling in the city. SItes filled with info so take a look. Smart shoppers probably want to head here or here to catch a discount...

January 23, 2008

Off the Waterfront

50 years ago NY was a city of docks. Just about it's entire history and rise stemmed from it's port. It's ability to connect mainland America to Europe, followed by the factories that piggybacked that transport network, the financial firms that swished the money around for everyone, the media companies that circulated the necessary information and the vibrant culture that grew out of that concentration of money, transport and people. Airplanes, container ships and interstate highways finally killed the docks though, and New York's water front slowly decayed and transformed itself into residential communities and parklands.

And for this moment it seems quite nice.

But we are staring straight into the face of an energy crisis. Two questions loom. When does the oil run out? And when do we have enough alternative fuels to not rely on oil? If those two dates overlap, well who cares, the path we are on will stay relatively smooth. But what if they don't.

Maybe, just maybe we'll need those docks back...

October 24, 2007

Photoshop by Committee

It's easy to just say design by committee. The story behind the new New York City Taxi graphics reads like a text book case. A firm makes a design. The client gives feedback. A new look comes in. Another firm comes late in the game with a new design element. A powerful department rejects a design for intruding on it's turf. The result is a sloppy hodgepodge of elements. Designers are rather predictably lining up to critique it.

Personally I rather like it. NYC Taxis have always had a sloppy mix of design elements on their side. Anything cleaner and neater, anything better designed, would threaten the only design element that matters. The bright yellow color screams "New York Taxi" louder than anything millions of design and innovation consulting fees could ever generate. As long as the cabs stay yellow, those taxis will look the same. What will never look the same again is NYC.

The new taxis provided a bit of political cover for an even bigger design project. New York City has a new logo. The suddenly infamous Wolff Olins designed it. and the new NYC taxis are the first place most New Yorkers have been exposed to it. Those taxis are design by committee, but that logo is something different. You can call it Photoshop by committee. Get used to it cause you'll be seeing a whole lot more of it.

What happens when you have a committee where every single member has a copy of Photoshop on their computer? Or worse yet every member has a designer on staff? Design by committee once broke down to a bunch of opinions and needs, all sorted out by one or two designers. The committee stacked up its requirements, its problems and its bullshit, and the designer cooked it all up into some bland result. A designer in that situation today would feel blessed.

What happens in Photoshop by committee is far worse. The needs and the problems and the bullshit are still there of course. But then comes the designs. Not just from the designer, but from the committee members. From their staff designers. From their assistants. From their teenagers and toddlers. From their neighbors, coffee shop baristas and dogs. Committees were once additive, the members just piled on the guidelines and suggestions and the designer boiled them down into a result. Now committees are recombinant. They warp, splinter and evolve into competing designs. The designer is barely the designer at all. They are the person who must make these mutations all work together.

Design by committee is about making rules. Photoshop by committee is about breaking rules. It's often the only way the designer can get the multiplying designs to recombine. Wolff Olins' professional salespeople call this "container logos" and it seems to be winning them some super premium clients. Most of us would just call it bullshit, but we aren't the ones with the super premium clients.

In the case of New York City what this amounts to is a big old smudge of the letters NYC. Not surprisingly it looks a lot like design from the early days of Photoshop. A design from an era where designers had no idea how to use the powertools in their hands. It's ugly and clunky and has nothing to do with NYC beyond using the letters. I love it. It follows none of the rules of design that stifle the profession. It's loud and bold and will show up in all sorts of places. Like the full NYC taxi design it graces, it will never step out of the shadows of a far bolder design, Milton Glaser's classic I (heart) NY logo. Is it great graphic design? Not at all. But it is great Photoshop by committee and it will work just fine.

August 08, 2007

Anticongestion Antipricing

Every once in a while a political issue rises up to put your various political beliefs to the test. As a cyclist and bicycle commuter in New York City I'm a huge advocate of Mayor Bloomberg's congestion pricing plan. As a pragmatist I like it even more, the track record of congestion pricing in London is stellar, this isn't just an idea du jour, its one that's proven to be both implementable and effective. Bloomberg sometimes moves with a speed that's shocking unpolitical, and he whipped the idea of congestion pricing in NY from a political dead letter to the hot issue of the day in months, and it was easy to get swept up in the enthusiasm. But then it ran straight into some classic legislative congestion in the form of the New York State legislature and all of a sudden no on has any clue where this plan is going. It's in that pause that I remembered one thing and realized another. One congestion pricing is some scary surveillance society shit, and two that there probably is a much better way.

While I'm on my bike I'm pretty much in favor of any idea that gets cars out of the way and away from me. Everyone has there own little biases, and I've come to realize I don't believe anyone behind the wheel of a car has any rights at all. They might be my favorite person in the world, but when they are driving (and I'm not in the car!) well they are just another one of those subhuman driver things... But congestion pricing is something of trojan horse for left, a concept that legitimizes extensive implementation of computer guided video surveillance, a vehicle to make our world feel a whole lot more 1984. Big Bloomberg is watching you, and making sure the streets stay nice and clear for those nice cyclists...

I've got a better idea, instead of building a massive infrastructure to watch the roads and bill the drivers a measly $8 a day, why not make driving in New York City (or at least Manhattan or in the legislative terms the CBD) truly expensive and clear the streets right out. Why not ban public parking? Just cut it out completely. Any vehical left unattended on a Manhattan CBD street gets towed. Real simple.

That's an extra two lanes on just about every street. You could make the left one a bike lane on every street for bonus points, but really I wouldn't even care. Wider streets with less cars would make NYC a cycling paradise with or without bikelanes. And at the rates garages charge in NY that will cut the amount of drivers radically, they'll be paying a whole lot more than $8 a day to drive around downtown that's for sure. Libertarians of all people have been getting hyped to a variation on this idea, but as per there style it's much more money obsessed. There version is that on street parking should be more expensive, that it should be charged at the market rate, in the libertarian eyes on street parking is a subsidized government privilege and they want the subsidy gone. I'll go further though. It's not the cheapness that's a privilege, it's the very existence of parking on the street. Maybe it made sense once, back in the day when cars were rare and stables more common than garages, but in this day and age the question we really need to ask is can cities afford to give that much public space over to parking private vehicles?

June 01, 2007

Postopolis

Postopolis at the Storefront for Art and Architecture, haven't made it yet ;( but I am giving a brief talk (like 5 minutes brief) talk there tomorrow. 4:30ish it seems, anticipated topic, Biggie Smalls, cause no one has told me other wise...

December 08, 2006

Localism

One of the odd things about the "anti-globalization" movement has always been that many, if not most of it's participants are not against globalization per se. After many travel across the world to protest, and some are rather active in campaigns to lessen, not strengthen many forms of border restrictions. It's been a well noted phenomena and sometimes the more accurate "anti economic globalization" phase is used, but never with much media traction, and inaccurate name has stuck. What makes it ironic though is a genuine anti-globalization movement just might be emerging, and out of a stock that overlaps only slightly from with the global protesters now stuck under a banner they didn't quite make themselves.

On can see it clearest in the local food movement, a movement rooted closer to the world of fine dining for rich people than with the anarchist squatters of the semi imaginary black block. It also is starting to show up with increasing vengeance in the writings John Thackara, who is reacting with perhaps unnecessary vigor and irony to the realization of the material impact of organizing international conferences in India has on the world. Of course neither the 100 mile dieters nor Thackara are the first localists, I'm sure it's an idea with century's of roots. But they do represent a crossing of a threshold, a movement of an idea from fringes beyond the pale and into fringes that actually touch base with the mainstream. How far it goes from here? Well you can mark this entry as a bit of radar tuning, it's a trend to watch not because I think it will be big or impactful, but because I have no idea where it goes next...

November 01, 2006

Pro-markets, Anti-profits

Pro-Markets, Anti-Profits

It's a statement so dangerously wrought with oversimplification that I've been avoiding saying it for a while now. But simplification can sometimes be as, or more, useful than oversimplification is dangerous, and nothing sums up my political economic stance better than reducing it to two positions: pro-markets, and anti-profits.

First and foremost this stance requires a split from a great mistake made by most traditional appwroaches to economics from critical marxism to laissez faire boosterism. Market activity and profits are not the same thing, but in fact too very separate forces and while they can and often do work in concert with each other, they do not always do so and certainly do not need to. If the goal of economics is to gain an understanding of how economies operate in order to improve them, and I believe that that has to be a major goal of economics, than coming to grips with this split is absolutely essential.

My stance may simplify down to "pro-markets", but it is essential that this stance not be confused with the far more common "pro-market" approach. The difference might on the screen or page be a matter of one letter, the addition or absence of an "s", but like many differences between the singular and plural this is actually a difference of nearly infinite ramifications. There are many (upon many) markets in this world, but "The Market" in the sense it is often used does not exist at all. Of course "the market" can exist in a very local sense, the way a mom might tell a kid to "go to the market and pick up a quart of milk." But "The Market" in the abstract sense that both proponents of "The 'Free' Market" and their many critics like to use it just does not exist at all. There are many markets in this world and the behavior of these markets in fact varies wildly. The baazar in Marakesh just does not function the same way the London Stock Exchange functions or the the way my local coffee shop functions. Heck, even the New York Stock Exchange functions differently than the NASDAQ market, and in fact there are even multiple markets for New York Stock Exchange stocks, each of which behaves slightly differently. The market for art at Sotheby's auction house is different than the market for art in a Chelsea gallery, which is different than the market in an Amsterdam gallery which in turn functions radically different than the nearby Dutch flower auctions.

A market is at it's core simply a place of exchange, a bounded area where people converge, either physically or via a mediating technology, in order to move exchange goods, services and information. To be pro-markets is to be in favor of the existence of markets, and to understand that each and every one of them behaves differently. Sometimes this behavior can have quite positive results, sometimes they can be rather negative and generally what reality gives us is a complex and nuanced mix of the two. Overall though markets are places of exchange and exchange itself is a healthy operation. By realizing that some markets behavior better than others we can begin the process of designing better markets, emphasizing those that work well and improving those that need work.

In order to evolve and create better markets, we need to make at least one key conceptual leap, me must break the historic tie between market functions and profit. Markets do not need profits in order to function at all. In fact it's possible to interpret profits in such a way that they are actually indications of an improperly functioning market, where the existence of profits indicates an inefficiency in market actions, a flaw that a more perfect market would correct. It's not an approach I'm about to follow, because perfect markets do not exist in the real world, and what I'm interested in is working markets, and the task of making them actually better.

Profit is perhaps one of the more unclear and misunderstood words in the english language. So much so that a large portion of the entire profession of accounting is dedicated to the art of obfuscating profits, pushing and shifting them around in ways that tend to be highly unprofitable to the public at large but rather rewarding to a select group of individuals. And just as profits can miraculously transform in the hands of a skilled CPA, the very meaning of the word has evolved in a rather confusing mash of economic theory and government action.

In classical economic theory, profit was deeply associated with the figure of the entrepreneur. Profit was how these idealized people would make their way in the world, they would purchase goods, transform or move them and then resell in a market. The difference between their expenses and the selling point, provided it was positive, was profit and this profit functioned as the entrepreneur's reward, salary and means to continue their business. It's quite a positive viewpoint of profit, and unfortunately it has little to do with the reality of how business is conducted and profits actually calculated today.

The entrepreneur as mythologized by classical economics barely exists anymore. Even those bold individuals who embrace the title today tend to wrap their enterprises in the protective skin of some form of limited liability corporation rather than proceed as sole proprietors or in traditional partnerships. Profits that pass through these organizations take on a radically different form than they do in the naive view of an entrepreneur. In fact even in a sole proprietorship or partnership profit transforms the minute that salary is introduced to the equation. For salary is after all an expense and profit is from a legal standpoint what occurs after all the expenses are paid. As soon as an entrepreneur is getting a salary, suddenly profit is no longer their just compensation for effort and risk, but in fact what is left over after they have been compensated for their time and work. Some of this profit is reinvested back into the enterprise of course, but all to often it is extracted from the system and into the hands of a limited set of individuals.

Classical economics is essentially about "individual profit", yet in this day and age while there are plenty of individuals making profits, it is almost always "organization profit" that they are making. Organization profit is not the organization's reward for good work, but in fact it's punishment, this is money that is extracted from the organization and back into private hands. It is still entirely possible to incorporate and run a business as a not-for-profit corporation, and that's an action with rather interesting ramifications. Such a business would not be eligible for federal tax exempt status in the United States, and it still could generate surplus revenues for which it would need to pay taxes, but those surplus revenues would not actually be profits. These revenues would have nowhere to go but back into the not-for-profit corporation. This is the corporate for as a (semi)closed loop system. There is still plenty of money going in and out as expenses and revenue of course, but ultimately the money flowing through the system must remain concentrated on the organizations goals and purposes. For profit corporations are not closed at all, but in fact function as the opposite, they are designed explicitly to function as money extraction machines concentrating wealth into the hands of a few individuals.

A certain type of reader might be tempted to look this view of profits as something akin to Marx's "surplus value", but nothing could be further from the truth. Marx's construction hinges upon a rather absurd and mythical idea of labor value, and ultimately views all surplus revenues as a negative. I however take the exact opposite stance, that surplus revenue is an incredibly positive thing, it is ultimately a key engine of economic growth. It is only when surplus revenue is transformed into "profit" and then extracted from the organizations that created that a real problem emerges. So while marxists like to see the economic problems of the world as being a function of "the market", I locate those problems in a very different place, in the hands of the individuals that skim off the top of market activity, and in the organizational forms that enable and encourage this behavior. This leads us to the second challenge of a pro-markets and anti-profits stance, how do we develop better organizational forms for economic activities?

The for-profit corporation in it's current form is less than 200 years old. It is only in the last century that it has truly erupted to become the dominant economic form in Western economies. There is no reason other than historical circumstance that it needs to be the dominant form now. In fact from the Korean chaebols to the Basque Mondragon Cooperatives there is plenty of evidence that other organizational forms can function on a global industrial level. In The Wealth of Networks Yochai Benkler has argued that the networked efforts of open source programers and wikipedia addicts represents a whole other economic organizational form. But ultimately I believe that's just the beginning. Organizations and markets are two forms of entities that exist on a scale larger than the individual. It makes them exceedingly hard to conceptualize, understand and transform, but they are ultimately the creations of humans and it is well within our means to improve upon them. Pro-markets and anti-profits, it is an over simplification for sure, but that is where I start.

October 02, 2006

The Ghost Map

When Steven Johnson says his next book is going to be about cholera, you can't help but be a little surprised. Yet while it has very little to do with Johnson's recent books on video games, television and brain machines, The Ghost Map is much less a departure and much more of a welcom return to the territory of his first two books. Follow the paths set by Interface Culture and Emergence till the point where they converge and you will find The Ghost Map. It's easily Johnson's best work yet and perhaps the first classic urbanist text of the new century.

The setting is precise, a handful of blocks in London's Soho neighborhood, late summer 1854. The stakes however are impossibly large, with London at the lead, the world in 1854 is getting increasingly urban, and the more urban it gets the greater the threat of cholera becomes. Cholera's vector of transmission is the digestive tract. It comes into the body through drinking water, and exits the other end, taking with it an extraordinary amount of a person's internal fluids, and usually their life with it. This leaves the cholera bacteria with a rather nasty biological challenge, it's main point of reproduction is the small intestine, yet getting from one person's small intestine to another is quite a journey. For most of history this meant cholera played quite a minor character.

As the industrial revolution pushed more and more of the world into cities, a unique opportunity for cholera arrived. When hundreds of thousands, or even millions of people squeeze into the tight streets of a city, their shit tends to flow downhill, and often straight into the same river that their drinking water is pulled from. The city literally began to function as a shit eating, or more accurately drinking, machine and cholera epidemics began to pop up regularly. The result was often tens of thousands of deaths in short periods of time. If the urban form was going to continue to grow, and all the pressures of the industrial age were pushing in that direction, it would need to deal with the problem of cholera. In London, in Soho, late summer of 1854 in a remarkable series of events the city essentially learned how to deal with cholera and this is the story of The Ghost Map.

Johnson approach to history clearly owes a certain debt to Manuel DeLanda's A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History but this book is almost it's inverse, centering on a highly specific point in time and space, and following a potent narrative. Perhaps you can call it "A Thousand Hours of Linear History". Those compact hours that form the core of the book are in a way an intricate tracing of something straight out of DeLanda's work, the crossing of a material threshold which then allows humans to settle into entirely new urban formations. For only by conquering, or at least learning to manage, cholera can people and cities evolve towards the massive scales we see today. DeLanda however labors hard to produce almost entirely material histories, invoking odd concepts like robot historians and the viewpoint of minerals themselves. Johnson follows something of this form when he talks about bacteria and cities, but then interjects two intensely human actors into the picture to produce a radically different sort of book.

The most striking academic parallel to The Ghost Map is not DeLanda's work at all but Bruno Latour's The Pasteurization of France. It's been a long time time since I cracked upon that tome, and honestly I'm not certain I ever finished it, but Latour is telling a strikingly similar tale to Johnson, tracing the complex interplay of factors that lead Louis Pasteur to his ideas and the world into adopting him. Latour of course is almost deliberately obtuse in his explorations, his goal at the time was to multiply the possible explanations, so once again Johnson again takes a somewhat inverted approach. Johnson is of course one of the clearest and must lucid of the current crop of science and technology writers. Given Latour's recent exhalation of the art of writing as core to the successful application of his Actor Network Theory, one has to wonder if Johnson may have inadvertently produced one of ANTs finest documents.

Like Latour Johnson breaks from the hero model of scientific discovery. But while Latour and his ANT practicing colleagues attempt to introduce as many actors, both human and non-human, into the story as possible, Johnson finds a much more coherent middle ground. The traditional telling of this story focuses around John Snow the lone scientist fighting against prevailing opinion, and Johnson does not try to discredit him, but instead adds three more actors to the stage, the microscopic cholera bacterium, the massive water infrastructure of London itself, and the very human and very social figure of Reverend Henry Whitehead. The result is a complex yet compellingly clear tale of social, scientific, organic and urban forces interweaving to produce both a tragic outbreak of disease and ultimately it's solution. It may well be the best book on urbanism since City of Quartz, yet way more optimistic, and well worthy of a space next to Jacobs on your urbanism shelf.

September 29, 2006

Identity and Identification in a Networked World / Ian Kerr

Identity and Identification in a Networked World started today. It's a free conference held only minutes from my home so my attendance stems mainly from convenience mixed with mild interest in the subject. That means I walked in without any expectations and that's great cause I walked out pleasantly surprised despite a rather uneven selection of talks.

Ian Kerr keynoted on the topic of DRM and was quite enjoyable. It was pretty much Adam Greenfield's Everyware rewritten by a law professor. The QA was frustratingly short, but from his quick answer to my question I have a sense he's way too far into the technodetermanistic side of life for my taste in the end, but he managed to provoke and stimulate quite well. I believe in a degree of technodetermanism too, but what frustrates me about those who take a harder version of it, is that they never seem to be able to grasp the concept of cultural responses evolving over time in order to deal with a problem.

Good thing Kerr is a professor, for he was far more entertaining and thought provoking than convincing. His whole argument about DRM somehow veered entertainingly into the world of shopping carts, via the example of carts that lock their wheels as they leave supermarket property. But is that digital rights management? Somehow it seems a bit more like physical rights management to me...

September 27, 2006

Saving Through Destruction

BLDGBLOG: City of the Pharaoh At the end of this pretty incredible post (not an unusual thing at BLDGBLOG) is mention of an archeological discovery from back in 1850. But by digging stuff up in 1850 was evidence we could use here in 2006 destroyed? Is our current archeological practice, so intent on discovering the secret past, actually destroying it as much as it is discovering it?

September 15, 2006

It's Only Value Is That It Has No Value

All my bicycles are street bicycles, there are no dirt trails, half pipes or beautiful mountain passes in their future, only the torn urban asphalt of New York City. But there a whole variety of urban bicycles out there, and my latest frame finally emerged from six months of bike shop limbo with a working bottom bracket, which gives me three bikes, or one too many for an apartment dweller like me. The only question is which bike to get rid of, and it's proving to be a trickier problem than expected.

From a purely bike riding perspective its an easy question, the one I call my neighborhood cruiser has practically no value at all, it's worth more as parts than as a complete bicycle and those parts are not worth much.** It shouldn't be too hard to part with, should it? But that is exactly the problem. I live in New York City and this bike is actually tremendously valuable based on the sole fact that it has no value.

This is a bike I can lock up on the street and not stress about in the least. I can, and do even leave it out overnight. From an economic standpoint this creates quite an interesting situation, a value that can not be monetized, for the very act of this feature taking on a monetary value would eliminate any value that existed. A bike with a real monetary value is worth stealing and that translates directly into both financial risk and psychological stress for a bike owner.

From a purely urban perspective this is an easy problem as well, the nicest bike, with the nicest parts has the least use in the city. Sure it's nimble and quick, and the Phil Wood hubs are both buttery smooth and the most capable of handling the urban grit and grime over a lifetime that via sale or theft will probably be far longer than I will own them. It's both a little to valuable and little too sensitive to be an everyday, no matter the weather, vehicle. It's tight track geometry can zig and zag through every urban obstacle, but it also translates every bump and crack in the road back to the rider with far more precision than comfort. It is quite literally a physical manifestation of the phrase "too much information". As beautiful as thing is to ride it tells me a bit more about the state of the streets beneath me than my body wants to know. But as much as I love the city this is far to sweet a machine for me to just let go of and so it stays, it's visceral aesthetics trumping pure practicality.

Tactically the best maneuver would to take the middle machine, and somehow make it "street stable", somehow degrade it's value to a point it can be left locked up along overnight without much stress. It's perhaps an impossible task, how do you devalue a bicycle without eliminating just what makes it a good, fun thing to ride? This is a frame that's been evolving into what might be called an "inverse hybrid", a new style monster uniquely suited for urban riding.

The bicycle industry currently pumps out some hideous beasts it calls hybrids, essentially overgrown mountain bikes designed to be ridden fully upright. Basically they make it easier to ride over potholes while sucking the joy out of every other aspect of urban bike riding. The inverse hybrid is the reverse, fixed gear gives you control and real sense of the road, while chopped riser handlebars put you in the ultimate urban riding position. Higher than the drop bars of a road bike, but lower and narrower than the chunky riser bars of a mountain bike. It handles almost like an overgrown BMX, if a BMX was capable of any real speed and efficiency on the city streets. It's a stance that gives a unique combination of maneuverability, visibility, hopping ability and just the right feel of the road in your hands.

The challenge now is to make an inverse hybrid that no one wants to steal. So just how do you make something that's only value is that it has no real value?

** This is particularly true at this time of year, the beginning of the fall and the end of the bike season. Odds are for a few months in the spring this bike will be more valuable than the sum of it's parts, only to lose that property as days begin to get shorter.

September 10, 2006

Emergence 06: Birgit Mager

Birgit Mager founded the first department of service design, at the Köln International School of Design and just now has founded the Sedes Research Center for Service Design Research. Her talk was quite good, a recapping of her work in Germany. At the same time it was a bit disappointing, Mager had been asking the sharpest questions repeatedly through the conference so I walked into the talk with expectations perhaps a bit too high. (But expectations always should be high!) Either way her work with the homeless in Köln is great.

random notes:

Gulliver: using service design to create a homeless center. "they found dignity there"

September 09, 2006

Emergence 06: Stefan Holmlid

Stefan Holmlid has the most intriguingly titled talk: "Introducing White Space in Service Design: This Space Intentionally Left Blank". Conceptually it's also the most enticing idea presented so far. Unfortunately though there is perhaps too much white space in Holmlid's talk, a bit too much left unsaid to stimulate the mind to the full extent of the concept. Still the core question is key, what is the roll of white space, blank space, empty space, in the design of a service.

Emergence 06: Chris Downs

Chris Downs of livework :: service innovation & design talked about the evolution of his company as the first ever service design consultancy. A good talk, they do good work, not sure what I can add.

random notes:

"service envy"

"try and speak the language of business and not design"

"difference between systems design and service design"

"system is really efficient but the service really sucks"

"we design more products now as service designers then we did as product designers, but we design them from a service perspective"

September 05, 2006

Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World

Picking up a copy of J.R. McNeill's Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World was my own personal response to my earlier question on how to deal with issues of scale. While I'm not quite sure it answered that particular question, I certainly can recommend the book highly and widely. It's quite simply the best thing I've read on the relationship between humans and the environments around us.

Of course I should note that I'm no expert, nor particularly well read on that subject. More than that though, it's a book that pretty much confirmed what I was thinking before I had stumbled across it in San Francisco's classic City Lights bookstore. Any book that tells you what you want to hear of course needs to be treated as suspect, but to McNeill's credit I suspect a lot of people with quite different viewpoints than mine would put down the book feeling similarly justified. That sounds contradictory of course, but McNeill is grappling with an enormously complex problem, one that is perhaps a bit too large for any one human to fully understand, and he does so in an incredibly clear and factual manner. He avoids preaching as best possible, and lays out a vast array of details spanning both history and nearly the entire scope of the earth, air, fire and water of our planet.

If you open up the book thinking the world is catapulting towards environmental disaster, you'll probably close it thinking McNeill has given you all the evidence you need to seal the deal. If you fall in the opposite extreme, if you think environmental problems are a figment of our imagination, well then actually you'll be disappointed with this book. But if your take is a bit closer to mine, that humans are capable of enormous problems, but also capable of solving just slightly more than we create, then well you'll find as much evidence of that as there is of the sky falling fast...

If there is a real problem with this book, it's probably that it's too damn short. It clocks in at a healthy 360 pages, but scope of facts and concepts compacted into those pages make it seem a bit meager. From tales of murderous fogs of coal smoke suffocating London and Pittsburgh to the stories of irrigation projects destroying entire seas, from war reports from the battlefields of the Green Revolution to deep sea journeys of whalers and fishermen, the book spins you around the globe enough to make the jet set jealous. In a slower time and place perhaps this book would have gotten the 800 or 1000 pages it deserves, but of course 21st century readers like me and you are probably both happier with and more likely to buy the 360 pages it actually delivers. Either way though I suspect the conclusion would be the same, sobering yet with just enough room for optimism to slip in:

It is impossible to know whether humankind has entered a genuine ecological crisis. It is clear enough that our current ways are ecologically unsustainable, but we can not know for how long we may yet sustain them, or what might happen if we do. In any case, human history since the dawn of agriculture is replete with unsustainable societies, some of which vanished but many of which changed their ways and survived. Perhaps we can, as it where, pile one unsustainable regime upon another indefinitely, making adjustments large and small but avoiding collapse...

August 29, 2006

The $300 Dollar Greens

A $300 dollar man was a draftee on the Union side of the US Civil War who opted to (and could afford to) pay a $300 fee in order to avoid military service. That's almost $6000 in today's dollars. Now imagine it's 1863 and you encounter a $300 man at a bar and get to talking and they start bragging about how much they are doing to fight against slavery. What would you think of such a person? Yeah, that's pretty much how I feel about this whole idea of "carbon neutral".

Sure the "$300 dollar greens" hearts might be in the right place, and there certainly are worse places their money can go, but just because it's cheap to buy off your conscious does not mean you can buy a real solution on the cheap, does it?

There are a whole lot of people out there in the world who just can not afford to go "carbon neutral". Would you rather help a person or plant a tree? That's a simple question with an infinitely complex answer, because helping the environment ultimately should help everyone on this planet is some small way. The health of the environment and the people who live in it are intricately tied together in ways more complex than we can easily untangle. Yet there is no doubt in my mind that an unhealthy chunk of the environmental movement is comprised of rich people buying a little peace of mind (aka ignorance) while protecting environments that most people in the world could never afford the carbon needed to visit, let alone afford to offset it somehow.

The bigger, more abstract and distant the problems, the easier it is to forget the real issues of inequality and poverty that stubbornly persist in the forgotten human environments of our own countries and cities. Yet as Majora Carter so intensely reminds us, these too are environmental problems. Hard problems, ones that won't go away by planting $300 worth of trees. Money is important, it can't be dismissed, but it can't be use to dismiss a problem either. These are problems that don't get solved by buying ugly lightbulbs, cramped cars and carbon offsets, they are problems that can only be solved by hard work, insight and maybe a little luck. So what are you doing with yourself and that $300?