May 09, 2009

ETF FAIL: Understanding Time/Volatility Decay in Short and Leveraged ETFS

There is a crack epidemic on the stock market. It trades by a variety of street names, FAZ, FAS, SRS, TZA & QID being just a few. Like crack cocaine these vehicles promise fast and stunning highs, one small hit can take you to the top. Occasionally they even succeed, but like crack cocaine these vehicles are doomed to collapse, each successive hit providing ever diminishing returns, lower lows that an addict believes they can only escape from via another hit.

Unlike crack there is nothing illegal about these things, they are short and/or leveraged ETFs. Exchange Traded Funds designed to replicate the effects of shorting various industries and trading with high amounts of leverage like the big boys do. ETFs are a very new concept to finance, they are basically mutual fund like entities that trade on the stock market, making them more liquid and more accessible to investors than mutual funds. They've been around for about two decades, but it's only in the last few years that they have really taken off in big numbers, with "innovative" short (aka bear) and 2x or 3x leveraged ETFs popping up left and right. Take a look at a chart for FAZ, the 3x Short Financial Industry ETF and look at the volume indicator on the bottom to get a sense how interesting in these things has exploded.

In 2008 leveraged bear etfs like FAZ were tickets to riches, as the stock market crashed they erupted in value, possibly making a few clever operators insanely rich. But that initial success quickly turned nasty. These ETFs are all flawed to the core, they are designed in a way that they decay over time, their values fluctuate up in down, but the overall tend is mathematically almost guaranteed to be down. The easiest way to see this flaw is the look at chart of a leveraged Bull and Bear pair over time. FAZ is a 3x Bear, it is designed to go up when financial industry stocks go down, and to return 3 times more than the value that those stocks go down. FAS is the 3x Bull counterpart, it is designed to go up when the financials go up, and to go up 3 times faster on a daily basis.

One would logically expect these two ETFs to cancel each other out, one goes up 3x when the other goes down 3x, so over time the net result should be zero. Yet if one looks at chart of these two mapped out over the past 6 months a very different picture is drawn. FAZ is down 94%, and FAS somehow is down too, by an almost as nasty 75%. Both are decaying rapidly taking their holders down to the bottom all because of a nasty mathematical quirk (or less generously flaw) in their design.

What's happening is volatility decay, these ETFs all lose value when the stock indexes they track are fluctuating up and down. The key to understanding why is a very basic mathematical fact relating to the way these ETFs are designed to reflect the daily percent changes of the parts of the stock market. The problem is that percents going up and percents going down don't always sync up, but instead have a distinct downward trend. This is easiest to see by looking at a 3x leveraged ETF. Lets call this ETF BSBS, and assume it's positively tracking the Bull Shit Index. When it starts both the index and BSBS are valued at 100. The next day the index goes up by 25% to 125. Now BSBS is designed to return 3 times that percentage or 75% so it goes up to 175. For a day at least it's a great investment vehicle. Now suppose the next day the index falls back down to earth, a 20% decline back down to 100. Well BSBS is now designed to go down 3x that or 60%. Now 60% of 175 is 105, a monstrous decline. The BSBS ETF is now all the way down to 70, while the index is still hanging in at 100. That's it in an essence, these things rise fast, but they fall even faster. It's that simple and that toxic.

The exact same thing is even truer with Bear ETFs. A non leveraged Bull ETF will actually have no volatility decay (although there are other smaller decays in their design). But the corresponding non leveraged Bear ETF will have a decay. Say you have a Bear ETP called UUPP designed to track the Bull Shit Index. Like BSBS it starts with both UUPP and the index at 100. Now say that the index goes down 25% to 75. Well that's why you bought UUPP, cause you wanted to sell that Bull Shit Index short and for a day you were right, UUPP goes up 25% to 125. Now the next day, the index doesn't behave and goes back up to 100, a 33.3% rise from 75. Well the index is back where you started, but was does UUPP do? It does down 33.3% from 125 to... 83.75. Yep, once again the ETF structure is screwing you. There is only one way in the end with these drugs and it's down.

Now one has to assume the ETF makers are well aware of these properties, yet they still sell the ETFs. Of course to protect themselves they warn the buyers, these ETFs are marketed as daytrader vehicles, things that should be bought and sold over the very short term, a few hours at a time maybe, if not a few minutes and a day or two maximum. Its a fair enough warning and not bad advice, but it's also a misleading warning. The reason is that there are circumstances where these ETFs are actually perform well over longer periods of time, and in 2008 we experienced some of these circumstances. Buying say QID (2x Short the Nasdaq index) in early 2008 and holding on to it for the year would have netted you a very healthy return.

When the stock market is trending very strongly in one direction, with very little volatility, just day in and day out moving the same way, than a leveraged ETF in that direction is going to produce stunning results. But stock markets rarely move smoothly, they stop, start, reverse, correct, roll sideways and then jump. They usually have some direction, but it's rarely and clear path, and it's the volatility that cracks you.

There is at least one more misleading thing about how these ETFs are framed as well, the way the term leverage is used. There are situations where an 3x "leveraged" ETF produces returns a similar result to being 3x leveraged (ie borrowing money to buy three times the amount of a stock than you have the cash for.) There are also situations where the results are quite different. Again it's the result of a basic mathematical effect/flaw in the ETF construction. Basically these ETF return numbers like classic leveraged situations when moving away from your baseline investment. However as soon as there is any reversion back towards that baseline the numbers begin to skew.

Say you have $100 that you want to use to buy XXX. But you want to make more money so you go borrow $200 more so you can buy $300 worth. That's classic leverage. If the next day XXX jumps up 25% to $125, well you now have $375 worth of stock and $200 in debt. Net result is being up $75 on a $100 investment, so you've made 3 times the 25% increase in the stock.

You could also buy XETF though an 3x ETF that tracks XXX. $100 worth, on day one would also go up 3x the 25% increase, so far so good, you've made triple profits without even borrowing money. Sounds a little too good to be true, no? It is. Cause say the next day XXX goes back to 100, a 20% decline. In the classic leveraged situation you go from holding $375 to holding $300. Minus your debt you are even (ignoring interest for simplicity.) Not great, but not bad either. But with the "leveraged" ETF, as we've seen before, that same 20% decline in XXX is going to have a different result. It will produce a 3x the percentage decline, so 60%. Now 60% of 175 is 105, so this ETF is decaying down to 70. Instead of being flat on your initial $100, like you would in a classic leveraged situation you are down 30. Just like a crackhead you just can't back to those initial highs like that can you?

January 18, 2009

The Tariff

So we are deep into a recession, with no particular end in sight. Obama has promised to jack up the governments debt already. The trade deficit is still stratosphere high. Tax cuts promised too, unemployment rising fast, and economists are worrying about deflation.

Something in those numbers doesn't add up, does it?

Right now the whole situation is staying afloat based on the fact that the US government can borrow money in a currency it also funnily enough can print itself. As long as they can keep doing that, deficits don't mean jack, we can get all the money it's shipping away back for the price of some paper and ink.

Then again the government has lowered interest rates to practically zero, how long will it be able to borrow money at those rates?

Raising rates means putting a squeeze on all the individuals and companies in the US currently deep in debt. Raising taxes to pay debts just sucks money out of the US economy. Maybe the economy just does a 180 and exports pick up, revenues rise and things correct. Or maybe the US Government really can borrow forever for free. Neither seems particularly likely though.

Things continue on a course like we see today and I have to wonder if we are charging fast towards the end of the free trade era. The government needs revenue, and they want to do it with taking that money out of the country's economy. The country needs jobs, the government is worried about deflation and the economy is net bleeding billions due to it's trade deficit. I'm not really one to predict the future, but are we looking at a big time return of the tariff?

edit (05/10/2009): Well a 100+ days past this entry and it's clear that tariffs are not high on the agenda, yet. It's all about the Federal government borrowing money and printing dollars and likely will be until either recovery or collapse of that system let's see how this plays out...

November 13, 2008

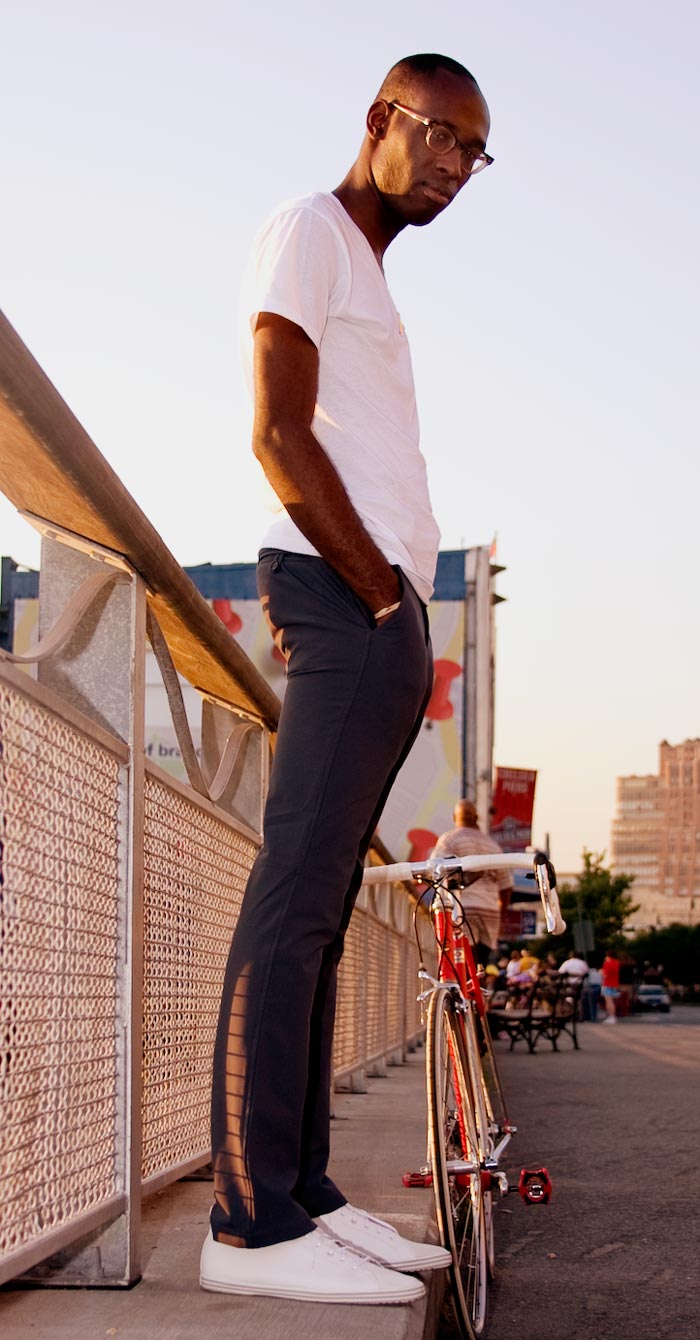

Outlier Tailored Performance

Outlier is my new venture. Probably find me writing a bit more there then here for a while. Outlier makes tailored performance clothing for cycling in the city. SItes filled with info so take a look. Smart shoppers probably want to head here or here to catch a discount...

October 01, 2008

Market to Marks

Hidden amongst this current financial crisis is a nasty little truth about neoclassical economics the hits to the core. This is the idea that economic objects should have one "market price" or equilibrium. The truth that lies in plain site is that this just isn't true. A bottle of orange juice might be a dollar in one shop, a buck fifty down the road and seventy five cents across town. There is a whole bullshit loads of talking around the clear fact of how this undercuts the very basics of economic theory. And there are also massive systems in place at stock and commodities exchanges, explicitly design to produce something as close to equilibrium prices as can be generated. But under this age's crisis all that cover falls clearly apart.

The issue is what is known as "mark to market", a system by which firms need to value their investments for accounting purposes based on the present market value of each financial object. And it needs to be done daily. In stable yet liquid market conditions this is generally a good thing, it promotes transparency and prevents firms from hiding bad investments behind dubious accounting practices.

However the system has fallen clean apart over the course of 2008. As firms get more and more risk adverse the liquidity for many investment vehicles has evaporated. The market value has plunged to zero, no one is out there that is willing to risk buying these things. Standard economic theory would have it that these things with zero market value are then financially worthless. But the fact is that they actually stand to return quite a bit of money over their lifespan. They have no market value in a risk adverse environment but have plenty of value to the firms holding them.

The mark to market rules have played at least some role in worsening the current financial crisis by exaggerating the losses in many firms. They are forced to report huge losses as the market value hits zero for their illiquid assets, yet these same assets will return at least some income over their lifespan. The SEC is currently "loosen" these rules, but just how so remains a bit unclear. Ultimately I can be almost sure they won't address the core issue though.

What really needs to happen is for economics to give up it's insistence on the idea of equilibrium pricing and acknowledge that markets can happily support a multitude of prices for any given object at any given time. It's no easy task because it essentially means scrapping a mass of economic theory and starting over from close to scratch. No easy task there, to say the least. But for a discipline that still can't answer Thorstein Veblen's 110 year old question of "Why is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science?" it's a completely essential step.

January 25, 2008

January 23, 2008

Off the Waterfront

50 years ago NY was a city of docks. Just about it's entire history and rise stemmed from it's port. It's ability to connect mainland America to Europe, followed by the factories that piggybacked that transport network, the financial firms that swished the money around for everyone, the media companies that circulated the necessary information and the vibrant culture that grew out of that concentration of money, transport and people. Airplanes, container ships and interstate highways finally killed the docks though, and New York's water front slowly decayed and transformed itself into residential communities and parklands.

And for this moment it seems quite nice.

But we are staring straight into the face of an energy crisis. Two questions loom. When does the oil run out? And when do we have enough alternative fuels to not rely on oil? If those two dates overlap, well who cares, the path we are on will stay relatively smooth. But what if they don't.

Maybe, just maybe we'll need those docks back...

January 20, 2008

Hype Check

Vampire Weekend - The album is not even "out" yet and it's already 6 months too late say that their parents listened to Paul Simon's Graceland too much while they were in utero. They might not steal quite as much from Africa as Paul but they do manage to sound even whiter than he does while in the act. I know they went to Columbia but the African guitars plus indie rock is genius enough that one wonders if they were in the MBA program. Good but not nearly as good as Boubacar Traore. I expect to be guiltily enjoying this while ordering americanos for years to come.

Lil' Wayne - If you say you are the best rapper alive enough times over and over again it just might come true. I'm pretty sure at least half the songs I listened to in 2007 came from a Wayne mixtape. Talk about the album not even being out yet... Fuck "In Rainbows" Wayne is the one blazing the trail for what the future of the music industry looks like. Sure no one quite knows where the money is coming from but you know it works out somehow. Main variable is just how long before Wayne's childstar symptoms take him down the Britney and Michael Jackson path. Plenty of warning signs out there, but so far his growing insanity seems to be more of the musically productive Prince variety...

The Cool Kids - I've been saying it for a while but the music industry really needs to look at the skateboard industry to learn how to monetize a product that's essentially free. The Cool Kids sound like some Columbia MBA realized the same thing and you know it works out somehow. If it comes out in a year or two that some streetwear company cooked them up to sell product I wouldn't be surprised at all. And as long as the beats stay hot I don't really care. As for the rhymes, not bad at all, but they could probably switch up the front men the way skate teams change riders and only the hardcore obsessives would care.

August 08, 2007

Anticongestion Antipricing

Every once in a while a political issue rises up to put your various political beliefs to the test. As a cyclist and bicycle commuter in New York City I'm a huge advocate of Mayor Bloomberg's congestion pricing plan. As a pragmatist I like it even more, the track record of congestion pricing in London is stellar, this isn't just an idea du jour, its one that's proven to be both implementable and effective. Bloomberg sometimes moves with a speed that's shocking unpolitical, and he whipped the idea of congestion pricing in NY from a political dead letter to the hot issue of the day in months, and it was easy to get swept up in the enthusiasm. But then it ran straight into some classic legislative congestion in the form of the New York State legislature and all of a sudden no on has any clue where this plan is going. It's in that pause that I remembered one thing and realized another. One congestion pricing is some scary surveillance society shit, and two that there probably is a much better way.

While I'm on my bike I'm pretty much in favor of any idea that gets cars out of the way and away from me. Everyone has there own little biases, and I've come to realize I don't believe anyone behind the wheel of a car has any rights at all. They might be my favorite person in the world, but when they are driving (and I'm not in the car!) well they are just another one of those subhuman driver things... But congestion pricing is something of trojan horse for left, a concept that legitimizes extensive implementation of computer guided video surveillance, a vehicle to make our world feel a whole lot more 1984. Big Bloomberg is watching you, and making sure the streets stay nice and clear for those nice cyclists...

I've got a better idea, instead of building a massive infrastructure to watch the roads and bill the drivers a measly $8 a day, why not make driving in New York City (or at least Manhattan or in the legislative terms the CBD) truly expensive and clear the streets right out. Why not ban public parking? Just cut it out completely. Any vehical left unattended on a Manhattan CBD street gets towed. Real simple.

That's an extra two lanes on just about every street. You could make the left one a bike lane on every street for bonus points, but really I wouldn't even care. Wider streets with less cars would make NYC a cycling paradise with or without bikelanes. And at the rates garages charge in NY that will cut the amount of drivers radically, they'll be paying a whole lot more than $8 a day to drive around downtown that's for sure. Libertarians of all people have been getting hyped to a variation on this idea, but as per there style it's much more money obsessed. There version is that on street parking should be more expensive, that it should be charged at the market rate, in the libertarian eyes on street parking is a subsidized government privilege and they want the subsidy gone. I'll go further though. It's not the cheapness that's a privilege, it's the very existence of parking on the street. Maybe it made sense once, back in the day when cars were rare and stables more common than garages, but in this day and age the question we really need to ask is can cities afford to give that much public space over to parking private vehicles?

March 11, 2007

All Free

Freebase is exactly the sort of thing that you only take seriously once you know Danny Hillis is behind it. Hillis is a bit of an underground hero in a world where many of his nerd peers skyrocket to fame in the business press, if not in popular culture as a whole. A nerd's nerd, his best known company went belly up in the 80's, his current one flies well under the radar and the NYT article linked above introduces him by mentioning his time as a Disney Imagineer, although it's never been clear he did anything notable there. But that first company was years ahead of it's time, his slim book Pattern on the Stone is easily the definitive text on how computers actually work and his Long Now Foundation one of the more audacious and mindboggling non-profits around (and one in which I'm technically a "charter member".) So yeah, when Danny Hillis launches a venture, you know the nerds at least are listening.

Freebase is the latest in a long series of essentially failed attempts to transform information into meaning. Or more specifically to transform computer readable information into computer readable meaning. Many have walked that path before, and in the end there is only one real success story, but that success story was Google with their Page Rank algorithm that made them a success. And like Google, Hillis is starting this venture with the best of intentions, and like Google Hillis is already starting say things that should make you very afraid.

The rhetoric of Freebase is all about freedom, openness and sharing. Everything about it says this is for you, this is for free this for the good of the world. Yet with a simple turn of a phrase or perhaps a slip of the tongue, Hillis lets on that he doesn't just want to share a lot of information, he wants it all. “We’re trying to create the world’s database, with all of the world’s information,” are his words and they probably sound familiar to anyone who has read a bit about Google over the past couple years. Despite loudly saying "don't be evil" Google is known to talk about the goal of "organizing all the world's information."* A phrase perhaps better suited for a cartoon supervillian than a large corporation.

The all might sound innocuous enough at first, until you place it into the context of Google's own actions. Perhaps you have a Gmail account, or at least send emails to someone who does. All the worlds info includes everything on those emails, do you want Google organizing all that information? The Gmail terms of service originally indicated that emails you delete might not actually be deleted off their servers, does that make "all the world's information" sound a little different then before? Some information is meant to disappear, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. Google it seems is not willing to make that distinction, although ironically they more than any other entity have the power to make things disappear. Instead of a situation were information is either available or not, we are creeping towards a world where information is either available through the front of Google, or it's only available the back, to those who can move through the backdoors of their databases.

Now I'm a huge fan of Hillis' work, and on a certain level Freebase is designed precisely to mitigate some of Google's emerging database monopoly, yet it's pushing forward with the exact same hubris that has made Google's "don't be evil" mantra such a sick joke upon the world. The rhetoric of freedom and openness may sound as universal as "all the worlds information", but it speaks to humans, while the information gathering is done by Turing machines. Hillis and the Freebase team are probably genuine in their interest in doing something for the world, but in the end they can only represent the interests of those that share their tech forward beliefs. Nestled safely in Silicon Valley it's probably easy to think the whole world shares those sentiments, but nothing could be further from the truth. The result it seems is a strange incubator where the supernerds slowly morph into supervillians, bent upon conquering the world (of information.)

*Google seems to have backed off this as public stance of late, but it still pops up on their site in places like their corporate philosophy page.

January 20, 2007

DJ Dramas || Parallel Economies

Close followers of hip hop, the music industry or the sidebar to this blog are probably well aware that the suddenly rather aptly named DJ Drama and his associate Don Cannon were arrested earlier this week and charged with the rather dubious felony of selling hip hop mixtapes. Drama was at the absolute top of his game, producing some of the most spectacular mixtapes of the past few years, most notably of late catapulting Lil Wayne into the role of hip hop's crown prince. Quite coincidentally (or perhaps not?) Drama was also about to receive some serious big journalism coverage, exposing the mixtape underground to a large audience almost completely outside it's standard base of operations. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) was the prime driving force behind Drama's arrest and quite clearly they saw a threat in both his own rise and in the rise of mixtape itself as both an artistic and economic endeavor.

Over the past couple years the mixtape industry has grown into a rather uneasy but working relationship with the traditional music industry that the RIAA represents. The mixtape world was a place to find new talent, test new songs, and build up street level buzz for artists. For artists like 50 Cent, T.I. and the Dipset crew the result was millions of dollars for both the artists and the record labels. Many of the songs on those mixtape cds may have been unauthorized and living in a legal gray area, but their existence was sparking the sales of those officiated CDs that make the dues paying members of the RIAA their money. That relationships clearly is no longer, although it's rather unclear whether RIAA ever quite realized what sort of relationship many of its member had with the mixtape industry, ironically enough DJ Drama was due to release his first major label back mixtape.

Culturally the RIAA's actions are about as hamfisted and assbackwards as it gets. They just went out and arrested a friend and associate of some of their best artists and members and alienated even more of their customer base. But economically it's a whole other story. The mixtape industry operates in what could be called a parallel economy. It's products circulate in shadowy networks, it's transactions off the record, it's details unreported. One can imagine situations where big rappers get paid by DJs to appear on mixtapes, and one can also imagine situations where rappers pay DJs to place them on mixtapes. What actually goes down is pretty much behind the scenes and off the books.

The music and mixtape industries may have had an uneasy but working relationship, but now that the RIAA has gone on the offensive one can see just who really threatened who. The music industry has been running scared since Napster first rolled on the stage like the chupacabra, and the mixtape world is just the latest, and quite possibly the greatest threat yet. Peer to peer file sharing threatened the music industry right were it hurt the most, the area of distribution, the point where the record labels were taking in all their money. But distribution is only one part of the music industries much larger business structure. They are also in the business of what they call A&R, the finding, filtering and amplification of new talent. They provide high risk financing to artists. They are in the manufacturing business, creating the physical products for sale. And they are in the marketing business big time, hyping up artists and getting them the attention they often want, and almost always need in order to sell large amounts of music.

What is some remarkable about the mixtape industry is just how thoroughly it threatens the established recording industry. The mixtape industry has a manufacturing base, the ability to make hundreds of thousands, and most likely millions of units. DJ Drama alone had 80,000 CDs taken from him during his arrest. More importantly though it has a distribution network, the ability to get it's products into the hands of retailers across the entire US, and those retailers are for the most part completely outside the RIAA's standard sphere of influence. Then there is the A&R, a role that mixtape DJs played so well that more than a few have been recruited to the major labels, and sometimes even given their own imprint to develop. All that the mixtape industry lacked was large artist development and marketing budgets of the major labels. But even with marketing the mixtape players were in all likelihood selling far more CDs per marketing dollar spent than the labels, and with that sort of result the artist development budgets might well be there sooner than later. In other words at least within the world of hip hop the mixtape industry has just about every component they need to replace the traditional music industry completely. If an artist can make as much or more money on the mixtape circuit why bother signing with a major label at all? Given how much more vital and exciting mixtape music is compared to the overproduced major label product it'd probably be a good thing. Of course a more likely result is probably closer to a semihostile merger/takeover than a slaughtering, but no wonder the RIAA is scared of the very mixtape DJs who are threatening to revitalize the world of music. The recording industry has lost everything on the cultural and artist side of things, all they have left is the money and lawyers to bully the real competition; at the expense of just about everyone else out there no less.

January 16, 2007

Authentic Counterfeits

When I read about counterfeit sneakers nowadays my first thought is "how can a get me a pair of those". Over the past few years the street, skate and sneaker industries have swiped a page out of the art world and mastered the science of manufacturing artificial scarcity. As a marketing trick it's probably got a long life ahead of it, there are always people around who want what they can not have regardless of of how obvious the artificiality of the process is. But as a story it's pretty damn, blah... Thousand dollar ostrich leather sneakers, limited edition of five? That's not exactly much more of a story than those five hundred dollar limited edition camel leather ones in an edition of 20 is it?

When it comes to telling a story you see, the counterfeits are the real deal, whatever authenticity they lack on the branding and legal sides they more than make up on their backstreets round the world journeys. From shady factories in the Pearl River Delta, through backroom deals cut in cities that may not have existed ten years ago, across oceans and through government checkpoints in a one skillfully packed two TEU shipping container with an artfully doctored collection of shipping papers, finally landing in ever shifting locations on the fringes of your hometown. The fashion companies may be toying with "pop up stores" but the bootlegger's move with a rapidity that authentic goods are in no shape to keep up with, and with a necessity the bootleggers must hate and fear but that real brands can only dream of obtaining.

As "design" continues to seep into every crevice of our culture, counterfeit goods also offer a level of authentic undesign that legal corporations are practically incapable of producing. The off the books and in the shadows production style might be focused upon replicating name brands, but it also generates an environment ideally suited for the art of the machine and the art of the accident to thrive. The counterfeit good is all about "brand", but it also lives free of a brand manager. It's all about design too, yet it is made without any concern to the designers intent. And in this freedom mistakes thrive beautifully. The counterfeiters may want to be as accurate as possible, but they lack the lines of communication to make that happen nor do they have much incentive to correct mistakes. The accidents after all damage only someone else's brand, and when they are capable of being sold they almost certainly are. Without the designers the machines are also set free, the counterfeiter's push them for accuracy, but without the designer's pushing them to meet the intent and not just the surface of the design, the machines can shape the form upon their own paths.

Once it's made, once it's shipped, once it's slipped past customs, once it's settled lightly in some temporary location, then you still need to find it. There are no insider announcements, no camping sessions lining up to buy the goods the second they hit the shop, no fevered eBay auctions for the newest of the new, and there is almost no way of knowing how many were made and how many more will follow. Value and excitement both tend come from the thresholds, and nothing navigates the thresholds of taste and legality like a counterfeit good. These are the real artifacts of the industrial age, the goods with real stories. Goods you can wear both with pride and without fear of harming their secondary market value. More authentic than any brand can hope for, welcome to world of the authentic counterfeit.

January 03, 2007

A Question for 2007: When is inequality a good thing?

The internet was supposed to be the great equalizer, the tool that would let anyone become a publisher, a news source, a movie director or the creator of even new medias. Shockingly enough in large part it succeeded and the predictions came true. Anyone on the right side of certain economics and techno-literate thresholds can indeed go online and distribute their works for little or no cost. We live in a world of publishers now and it's great in many ways, for one it enables this blog to exist. Yet something also went horribly awry in the process. We got everything the internet promised, everything except the equality.

In a world of millions of news sources we still focus our attention on a select few. There has been a bit of a reshuffling at the top for sure, new information powerhouses have stepped up and dominated, while some of the old media players have stumbled while others danced nimbly into newly global audiences. But information continues to follow a power law curve, which roughly means we focus 80% of our energies upon what emits from just 20% of the providers, and the top 1% command half of our total attention. Wealth too follows this distribution, with the super rich dominating absurd amounts of the world's cash flow, and the payouts to the top dogs at the likes of Google, MySpace and YouTube only reinforce this inequity.

Equality is a concept wrought with it's own inequities. We pay incredible lip service to it as a concept, but rarely implement it well in reality. There are only a few people willing to defend say the extreme difference in earnings between top Wall Street executives and the entire quarter of New York City's population that lives below the poverty level while also living in one of the world's most expensive cities. But there are few still who are actually willing to do something about it.

One of the ironies of inequality is that it's almost always looked at a bad thing, when in fact it often is exactly the opposite. Take your blood for example. You may have left small drops from cuts and scratches around your childhood haunts. You've probably given a few samples that now sit in testing labs or medical disposal sites. You might have donated a few pints that now sit in blood banks or circulate in some form through another persons body. But the vast majority of your blood stays within your body and you wouldn't want it any other way, would you? Your blood evenly distributed across the globe wouldn't do anyone much good, would it? That globe of course is an inequality in itself, stars, planets and atmospheres are ultimately the result of a radically unequal distribution of elementary particles.

Equality of course can also be stunningly boring. We wouldn't want all flowers to be equal in shape and coloring, nor do we enjoy it when every building looks the same. But none of that takes away from the fact that the inequalities of power, wealth and culture we tend to focus on have awful and far reaching consequences. Consequences we don't often actually address. There is a danger in shifting more attention towards the overlooked space of positive inequalities, a risk of de-emphasising the existing problems even further than they are now. But with that risk comes the potential to find solutions. Perhaps, but just perhaps, the fact that so little is actually done to address the radical inequalities in America and beyond stems from that discord between the idea of inequality being bad and prevalence of subtle examples of where it isn't. More than that though is the prospect that somewhere within the examples of positive inequality lies an answer, or at least a start of answer to how we can transform the negative inequalities around us into a better state of being.

So it's 2007 now, maybe ask yourself, when is inequality a good thing?

December 31, 2006

The Long Tale of 2006

2006 is racing to a close and you may well be aware that Time Magazine has named "you" person of the year. If you work for a financial firm on Wall Street, in the City of London or on whatever expensive piece of real estate you've landed you probably could have figured that out by looking at your record breaking bonus check. Of course if you worked in New York's financial industry you were already making over $8,000 a week before that bonus even kicked in.

Across the East River from Wall Street there are parts of Brooklyn where the average household income per year is less than that average wall streeter is making each week. If you lived in one of those household you might be a bit more surprised about being named person of the year, no? Of course this radical inequality in income distribution isn't exactly news to anyone, it's been around ages and statically mapped out by the Italian economist Vilfedo Pareto about a century ago. If you graph that distribution out what you get is something called a power law curve. In 2006 though the trendy terminology was "the long tail", a phrase for just one part of the power law curve, the part where those of us making less than $8,000 a week happen to reside.

The long tail is in large part a phrase created and popularized by Wired Magazine's Chris Anderson in a book and blog of the same name. While I doubt Anderson intended it as such, the long tail is one of the more misleading pieces of rhetoric around. What Anderson wants to focus on is the stuff that drives Time magazine's "you", the increasing world of user generated content, movies, sound files, Flash animations, blog posts and all the other amusing detritus of unknown quality filling out the internet. And there is no denying that this stuff is exploding, sometimes in quite interesting ways. But what makes the long tail so disingenuous is that what happens in the long tail has almost no ramifications on what happens in the head. The language of the long tail often takes on the rhetoric of democracy or even revolution, but the fact is that nothing about the influx of user generated content necessarily impacts the inequalities encoded into the power law curve. If anything the long tail presupposes inequality, and Anderson is in essence saying "pay no mind to the inequalities at the top of the internet, look at all the exciting stuff over here in the tail".

Of course it's become increasingly apparent that the internet is wrought by, if not outright characterized by inequality. Web traffic is even more concentrated to the largest web sites.* Of course a couple of those top 10 sites are actually places like YouTube and MySpace where large amounts of user generated content drives traffic and then deposits money in hands not of the creators, but instead in the coffers of the large corporate landlords. Nicholas Carr aptly compares this setup to sharecropping. One can see foreshadowing of this effect in Chris Anderson's writing, for all his hyping of the long tail he sees far more concerned with creating the structures and situations in which long tails can occur than he is concerned with what things might actually be like inside those long tails. The owners of the MySpaces and Flickrs and the producers of video editing softwares are getting rich by enabling an unprecedented amount of people to make and distribute their own 'content'. And way off at the edge of these systems are a few alpha users who also may be getting rich, or at least famous to their peers by making some of that content. They aren't in the long tail though, they are in privileged head. Those in the tail might have a little fun, but they get neither the audience nor financial rewards that demarcate success in this 21st century culture.

No matter how you spin the long tail, and without a doubt there are aspects of it that are interesting and perhaps even admirable, you can't detach the long tail from the power law curve that it is part of. And as long as we are talking about a power law curve, we are talking about radical inequality. Unfortunately that's something that's predated 2006 for quite some time and doesn't look to be leaving with the new year either...

- If you follow that link though, you might notice the story has a rather misleading headline "The Shrinking Long Tail - Top 10 Web Domains Increasing in Reach". That the top ten domains are increasing in reach is a fact, at least if the statistics in that article are correct, but that fact has no correlation the long tail shrinking or rising in any manner. It's perhaps easier to think about it in terms of income. When the rich get richer, does that mean there are less poor people or more? That's just not a question that can be answered without more information. The top websites are getting richer for sure, both in terms of money and in terms of attention paid to them, but there may well be millions of new tiny sites stretching the tail out further and further.

December 30, 2006

Scarcely Economics

The cliche goes that the flapping of a butterfly wing in Asia just might be the movement of air of that triggers a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. The math of that cliche is relatively developed, but it's mainly a computer simulation situation, actually showing the effect of those flaps is a beyond our sensors...

Somewhere on the edge of academia circulates the idea that economics is defined as the "study of how human beings allocate scarce resources". It's a definition that doesn't show up in most dictionaries, but it has a stubborn persistence. Scarce resources are of course an important component to economics, but is it really all there is? Most definitions instead fall rather close to Webster's: "a social science concerned chiefly with description and analysis of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services."

It's a curious distortion to make economics strictly a study of scarcity, and like the textbook chaos theory case it starts out as a rather minor disruption. Scarcity is after all essential to the generation of price and value, and economists hold those processes dear to their hearts. There is of course more to economics than just studying scarcity, but it's not exactly an alien concept. What's curious is what happens when non economists start latching onto the distortion, what's curious is when scarcity meets attention from three different directions.

Michael Goldhaber, Richard Lanham and Georg Franck, all more or less independently converged on a phrase, "the economics of attention" in the past decade or so. At the core of their thought (which varies widely in quality) is the observation that in a time where information is becoming, in Goldhaber's terms, "superabundant" what is scarce is attention. It's an interesting observation, one well worthy of economic exploration, but oddly enough Goldhaber, Lanham, and, from what I can tell without reading German, Franck as well all want to go much further. They pull back and wheel up with their distorted version of economics as being solely the study of scarce resources. It's a funny equation, an interesting observation plus a distorted definition equals a call for a whole new construction of economics.

The first irony is that if economics was really just to be about the distribution of scarce resources it wouldn't even be about money. For money is about as far from a scarce resource as there is. It can be printed out by any government and by a skilled counterfeiter too. Or it can be generated by any group or organization with enough clout. Airlines for instance have essentially created their own currencies of frequent flier miles, while towns like Ithaca, New York have created their own regional currencies with little more than a printing press and a PR campaign. Of course in this digital age a printing press is way to heavy, banks of course can famously create money by lending out money that people deposit for savings and in the twenty first century this operation has been extended into financial maneuvers of baroque complexity that span the globe in seconds. Money is anything but scarce. The problem is not there is not enough, but that it circulates with a damaging inequality.

Goldhaber and Lanham though don't seem really want economics to be about money anyways though. They'd much rather refocus it all around attention. It's an act of overstatement that probably does them far more harm than good. They get to make exaggerated statements about the need for a new economics, perhaps it makes their observations seem bigger, but it also makes it far easier to ignore them. They might want it all to be about attention, but quality and accuracy still have a bit of value left in them. Someone is going to make a career pulling attention scarcity into the wider economic stream of thought, but it just wont have the extreme ramifications the attention lovers vest into it. Goldhaber's work in particular is still worth of future attention, but until he pays a bit more attention to what economics actually is his insights will probably remain obscure to the discipline...

November 11, 2006

Irreversibly Google

The story of Google is in many ways the archetypal engineer's dream. They invented a better way search the web, set up in a garage-like space and rose to the top. But engineer's also value results that can be reproduced, and part of what makes Google so scary is that it can not be reproduced. As hard as Yahoo and Microsoft are trying, with obscene amounts of financial, engineering and computing resources at their disposal they can't generate search results as good as Google's. The search world is already oligarchical, but as google rapidly turns into a verb, it is well on it's way to become a monopolized space.

Page Rank you see is an irreversible and an irreproducible process. Page Rank is the name for the key aspect of Google's search algorithm, the engineering breakthrough that make Google so much better than all those now dead or battered search engines of the 1990's. And it's also the thing that makes it so damn hard, if not impossible to make a search engine as good as Google's. You can reverse engineer Page Rank of course and you can be damn sure both Yahoo and Microsoft have invested plenty of time to that effort. The problem though is that Page Rank just would not work if you ran it today, and that's why Yahoo and Microsoft just can't provide the same quality of results as Google.

At it's core it's a problem of the data set. Page Rank's big break through was that it realized that links between webpages could be used as a way to judge the quality of a piece of content. If a page was linked to by multiple sites odds are it was a better page than one with no incoming links. Furthermore if the links came from other high quality pages the odds would be even higher. I wrote that all in the past tense though, because Page Rank is a victim of it's own success. The internet is now filled with massive amounts of pages generated with the explicit goal of hacking Google, of pushing sites up higher in it's search results. The internet as a dataset is now dirty, if not filthy.

This is a problem for Google of course, but it's not nearly the same problem it is for them as it is for it's competitors. Google needs to deal with the many sites trying to hack it's results, but it has a major tool to fight them, the data generated by Page Rank before search engine optimization became a profitable and fulfilling career. It means Google weighs slightly towards older sites, ones established in the era of clean Page Rank, but it also means that anyone trying to reproduce Page Rank by spidering the internet today, just can not get results nearly as good as Google's. So until someone devises a brand new algorithm, it's going to be Google's internet and the rest of us are just searching for our own small little piece of it...

November 01, 2006

Pro-markets, Anti-profits

Pro-Markets, Anti-Profits

It's a statement so dangerously wrought with oversimplification that I've been avoiding saying it for a while now. But simplification can sometimes be as, or more, useful than oversimplification is dangerous, and nothing sums up my political economic stance better than reducing it to two positions: pro-markets, and anti-profits.

First and foremost this stance requires a split from a great mistake made by most traditional appwroaches to economics from critical marxism to laissez faire boosterism. Market activity and profits are not the same thing, but in fact too very separate forces and while they can and often do work in concert with each other, they do not always do so and certainly do not need to. If the goal of economics is to gain an understanding of how economies operate in order to improve them, and I believe that that has to be a major goal of economics, than coming to grips with this split is absolutely essential.

My stance may simplify down to "pro-markets", but it is essential that this stance not be confused with the far more common "pro-market" approach. The difference might on the screen or page be a matter of one letter, the addition or absence of an "s", but like many differences between the singular and plural this is actually a difference of nearly infinite ramifications. There are many (upon many) markets in this world, but "The Market" in the sense it is often used does not exist at all. Of course "the market" can exist in a very local sense, the way a mom might tell a kid to "go to the market and pick up a quart of milk." But "The Market" in the abstract sense that both proponents of "The 'Free' Market" and their many critics like to use it just does not exist at all. There are many markets in this world and the behavior of these markets in fact varies wildly. The baazar in Marakesh just does not function the same way the London Stock Exchange functions or the the way my local coffee shop functions. Heck, even the New York Stock Exchange functions differently than the NASDAQ market, and in fact there are even multiple markets for New York Stock Exchange stocks, each of which behaves slightly differently. The market for art at Sotheby's auction house is different than the market for art in a Chelsea gallery, which is different than the market in an Amsterdam gallery which in turn functions radically different than the nearby Dutch flower auctions.

A market is at it's core simply a place of exchange, a bounded area where people converge, either physically or via a mediating technology, in order to move exchange goods, services and information. To be pro-markets is to be in favor of the existence of markets, and to understand that each and every one of them behaves differently. Sometimes this behavior can have quite positive results, sometimes they can be rather negative and generally what reality gives us is a complex and nuanced mix of the two. Overall though markets are places of exchange and exchange itself is a healthy operation. By realizing that some markets behavior better than others we can begin the process of designing better markets, emphasizing those that work well and improving those that need work.

In order to evolve and create better markets, we need to make at least one key conceptual leap, me must break the historic tie between market functions and profit. Markets do not need profits in order to function at all. In fact it's possible to interpret profits in such a way that they are actually indications of an improperly functioning market, where the existence of profits indicates an inefficiency in market actions, a flaw that a more perfect market would correct. It's not an approach I'm about to follow, because perfect markets do not exist in the real world, and what I'm interested in is working markets, and the task of making them actually better.

Profit is perhaps one of the more unclear and misunderstood words in the english language. So much so that a large portion of the entire profession of accounting is dedicated to the art of obfuscating profits, pushing and shifting them around in ways that tend to be highly unprofitable to the public at large but rather rewarding to a select group of individuals. And just as profits can miraculously transform in the hands of a skilled CPA, the very meaning of the word has evolved in a rather confusing mash of economic theory and government action.

In classical economic theory, profit was deeply associated with the figure of the entrepreneur. Profit was how these idealized people would make their way in the world, they would purchase goods, transform or move them and then resell in a market. The difference between their expenses and the selling point, provided it was positive, was profit and this profit functioned as the entrepreneur's reward, salary and means to continue their business. It's quite a positive viewpoint of profit, and unfortunately it has little to do with the reality of how business is conducted and profits actually calculated today.

The entrepreneur as mythologized by classical economics barely exists anymore. Even those bold individuals who embrace the title today tend to wrap their enterprises in the protective skin of some form of limited liability corporation rather than proceed as sole proprietors or in traditional partnerships. Profits that pass through these organizations take on a radically different form than they do in the naive view of an entrepreneur. In fact even in a sole proprietorship or partnership profit transforms the minute that salary is introduced to the equation. For salary is after all an expense and profit is from a legal standpoint what occurs after all the expenses are paid. As soon as an entrepreneur is getting a salary, suddenly profit is no longer their just compensation for effort and risk, but in fact what is left over after they have been compensated for their time and work. Some of this profit is reinvested back into the enterprise of course, but all to often it is extracted from the system and into the hands of a limited set of individuals.

Classical economics is essentially about "individual profit", yet in this day and age while there are plenty of individuals making profits, it is almost always "organization profit" that they are making. Organization profit is not the organization's reward for good work, but in fact it's punishment, this is money that is extracted from the organization and back into private hands. It is still entirely possible to incorporate and run a business as a not-for-profit corporation, and that's an action with rather interesting ramifications. Such a business would not be eligible for federal tax exempt status in the United States, and it still could generate surplus revenues for which it would need to pay taxes, but those surplus revenues would not actually be profits. These revenues would have nowhere to go but back into the not-for-profit corporation. This is the corporate for as a (semi)closed loop system. There is still plenty of money going in and out as expenses and revenue of course, but ultimately the money flowing through the system must remain concentrated on the organizations goals and purposes. For profit corporations are not closed at all, but in fact function as the opposite, they are designed explicitly to function as money extraction machines concentrating wealth into the hands of a few individuals.

A certain type of reader might be tempted to look this view of profits as something akin to Marx's "surplus value", but nothing could be further from the truth. Marx's construction hinges upon a rather absurd and mythical idea of labor value, and ultimately views all surplus revenues as a negative. I however take the exact opposite stance, that surplus revenue is an incredibly positive thing, it is ultimately a key engine of economic growth. It is only when surplus revenue is transformed into "profit" and then extracted from the organizations that created that a real problem emerges. So while marxists like to see the economic problems of the world as being a function of "the market", I locate those problems in a very different place, in the hands of the individuals that skim off the top of market activity, and in the organizational forms that enable and encourage this behavior. This leads us to the second challenge of a pro-markets and anti-profits stance, how do we develop better organizational forms for economic activities?

The for-profit corporation in it's current form is less than 200 years old. It is only in the last century that it has truly erupted to become the dominant economic form in Western economies. There is no reason other than historical circumstance that it needs to be the dominant form now. In fact from the Korean chaebols to the Basque Mondragon Cooperatives there is plenty of evidence that other organizational forms can function on a global industrial level. In The Wealth of Networks Yochai Benkler has argued that the networked efforts of open source programers and wikipedia addicts represents a whole other economic organizational form. But ultimately I believe that's just the beginning. Organizations and markets are two forms of entities that exist on a scale larger than the individual. It makes them exceedingly hard to conceptualize, understand and transform, but they are ultimately the creations of humans and it is well within our means to improve upon them. Pro-markets and anti-profits, it is an over simplification for sure, but that is where I start.

October 27, 2006

Waistline Banging Like a Bassline

You can call it a general lie, a lie so big yet so harmless that no one really cares that it's a lie. Like many American boys and to a lesser extent girls, I was introduced to the general lie via comic books. Comics for whatever reason tend to arrive in the stores about three months before the date on their covers. I've never heard the definitive story as to why, but the common explanation is that it makes them seem newer, but really, even avid comic book fans don't really think they are getting shipped in from 3 months in the future do they? Instead they just accept the general lie, a small quirk of a medium that thrives on quirks.

I've been slowly testing and exploring a venture into producing a line of clothing and it's there I stepped upon another general lie. One that lies around the waistline. Women's clothing comes in more or less abstract sizes, a size 2 or size 12 connotes nothing in itself, any information it communicates comes from it's relationship to the other sizes and to past experience trying on clothing of a similar number. Men's clothing on the other hand is often sized in inches, a shirt with a 16 and 1/4 inch collar, a pair of pants with a 34 inch waist and 32 inch inseam. These are numbers I always took for granted where pretty much true, and sometimes they even are. But when it comes to the waistline, well the truth is far fatter than the numbers, at least when it comes to American (and British) garments... About four inches fatter by my calculation. A size 32 waist in a garment is closer to 36 inches on the tape measure, a 34 closer to 38...

Has it always been this way? I doubt it. When I told my patternmaker that the first sample would be a 32, she took it literally, on her side of the garment industry the numbers don't lie. The lies don't start till the inside of some factory, maybe it's in Guatemala, maybe in Turkey, maybe in China, maybe in a few cases even in the US still. There the garments are put together under one number and with just a few swift stitches to a label walk out under another number altogether. All for the sake of protecting the male ego it seems, for at least in the eyes of the garment industry Americans just can't handle how fat we are getting...

As I inch closer to actually producing garments, this presents an interesting dilemma. I could tell the truth, sell pants with the actual waist size labeled. But to do so would mean I'd be out there making people feel fat as they try on my clothes, not exactly the best sales tactic, no? More than that I'd be paddling upstream, pitching garments that just don't fit the way people expect them too, despite being more honest about their size. One can imagine comic publishers faced with a similar dilemma as they slowly inflated the dates on their covers. On one hand they all knew the dates where a farce, yet at the same time no one could turn back without risking looking like they where behind the times. So as the American waistline slowly creeps up undercover of the garment industry, don't blame me, I'm just following the crowd towards bigger and better things...

October 10, 2006

Economics/Attention

It's the year 2006, how do you get away with publishing a book without ever googling your title? I have no idea but Richard Lanham's new book The Economics of Attention curiously has no references at all to Michael Goldhaber's The Attention Economy: The Natural Economy of the Net, hmmmm. Goldhaber's work was published online in a peer-reviewed journal nine years ago. It's core premise is practically identical to Lanham's. Google the title of Lanham's book and Goldhaber shows up as the third full result, behind only references to Lanham's book. I'm all of nine pages into that book so who knows how it stacks up, but it sure hasn't started out right, at least if your a nerd like me who reads the bibliography first...

October 09, 2006

"Corporate Social Responsibility" and the "Bottom of the Pyramid"

Can a corporation have a conscience? Nobody really asked that at Columbia Business School's Social Enterprise Conference 2006, but the question underlaid it all uneasily. Well, at least for me. The fact that the conference exists at all clearly indicates that plenty of business school students have some conscience, but they fact that they are in business school in the first place also clearly indicates that conscience is modulated by a certain faith in enterprise.

The buzzword that resonated loudest to me in this buzzword filled environment was "corporate social responsibility" or CSR for short. The idea is that companies need to healthy citizens or something, but in practice it seemed more like a way for people embedded deep in giants like Citicorp or Alcoa to soothe their own consciences with a small diversion from the corporate cash flows. Strikingly absent from the discussion was any sense of how CSR spending, when it exists at all, might stack up against the rest of these giant's budgets.

Jim Sinegal, the CEO of Costco, at least talked real numbers as he accepted an award of some sort. He proudly threw up a quote about how it was better to be a Costco employee or customer than a shareholder. The Costco philosophy is to cut costs everywhere except when it comes to employees, who if I remember his sliders correctly represent 70% of the companies operating cost! But even as he deflected personal credit away from him and out towards his entire management team it was quite clear this approach is merely an iteration of the age old concept of the enlightened dictator. The employees/serfs may be happy, but only because the situation is enforced from the top. Like his counterparts at the head of Starbucks and American Apparel, Sinegal has no structure in place to ensure that his enlightened approach can be anything other than a management decision.

This situation has deep roots in the history of management theory, it's something of a Taylorism versus Fordism approach. Happy employees is clearly a successful business style, but so is the far more exploitative bean counting tight ship way of management. Costco might be better for employees than Wal-Mart, but both still are out there and both perpetuate hierarchies that pump money into a small upper class. Some kings were better to their serfs than others, but either approach meant the existence of a kingdom. And I don't think it's a coincidence that the corporate organizational form emerged just as democracy began to unstabilize the aristocracies of old.

It's not the aristocratic side of this corporate finishing school that's really disturbing though, it's the religious one. Most people in these environs have some sense, however watered down, of their privilege and the larger inequalities out there. It's the people who truly have a faith in "The Market" that really freak me out. The ones that really believe that "CSR" will spread because consumers demand it or scarier still those that believe in BOP. BOP stands for the "bottom (or sometimes "base") of the pyramid", the billion strong poorest of the poor. The idea is that by turning these people into entrepreneurs partnered with multi-national corporations and selling to their equally poor peers poverty can be eradicated.

One of the key mantras of BOP believers is that it can not be reduced to just selling goods to poor people, but instead requires a far more intense and interlocking relationship with the target market. This is absolutely true. What BOP is about is not selling products, that's just a corollary to all. What it is about is selling an ideology. Like the centuries of missionaries before them the BOP proponents think they are saving when actually they are converting.

Poverty is an issue with far more ramifications than can be explored here, but the simple point is that not having a lot of money can only be seen as an absolute bad thing if you follow a faith that revolves around the accumulation of wealth. Certainly there are probably problems that we as westerners see in the populations at the "base of the pyramid" that the people themselves might also agree are problems. But there are also problems that are far less physical and far more religious in nature. Like the heathens of old these are people with different value systems than us, and like missionaries trying to save souls, it's quite likely some of the problems the BOP practitioners are out trying to solve are only problems of faith. And as well meaning as they may be I for one have no faith their little enterprise...

October 08, 2006

Random Question

Why is it that anytime you read about the advertising or video game industry, both of which are massive profitable and pretty much icons of our culture, they always claim to be struggling? Are industries based upon rapid fire information inherantly less stable than ones based on selling material goods?

September 15, 2006

It's Only Value Is That It Has No Value

All my bicycles are street bicycles, there are no dirt trails, half pipes or beautiful mountain passes in their future, only the torn urban asphalt of New York City. But there a whole variety of urban bicycles out there, and my latest frame finally emerged from six months of bike shop limbo with a working bottom bracket, which gives me three bikes, or one too many for an apartment dweller like me. The only question is which bike to get rid of, and it's proving to be a trickier problem than expected.

From a purely bike riding perspective its an easy question, the one I call my neighborhood cruiser has practically no value at all, it's worth more as parts than as a complete bicycle and those parts are not worth much.** It shouldn't be too hard to part with, should it? But that is exactly the problem. I live in New York City and this bike is actually tremendously valuable based on the sole fact that it has no value.

This is a bike I can lock up on the street and not stress about in the least. I can, and do even leave it out overnight. From an economic standpoint this creates quite an interesting situation, a value that can not be monetized, for the very act of this feature taking on a monetary value would eliminate any value that existed. A bike with a real monetary value is worth stealing and that translates directly into both financial risk and psychological stress for a bike owner.

From a purely urban perspective this is an easy problem as well, the nicest bike, with the nicest parts has the least use in the city. Sure it's nimble and quick, and the Phil Wood hubs are both buttery smooth and the most capable of handling the urban grit and grime over a lifetime that via sale or theft will probably be far longer than I will own them. It's both a little to valuable and little too sensitive to be an everyday, no matter the weather, vehicle. It's tight track geometry can zig and zag through every urban obstacle, but it also translates every bump and crack in the road back to the rider with far more precision than comfort. It is quite literally a physical manifestation of the phrase "too much information". As beautiful as thing is to ride it tells me a bit more about the state of the streets beneath me than my body wants to know. But as much as I love the city this is far to sweet a machine for me to just let go of and so it stays, it's visceral aesthetics trumping pure practicality.

Tactically the best maneuver would to take the middle machine, and somehow make it "street stable", somehow degrade it's value to a point it can be left locked up along overnight without much stress. It's perhaps an impossible task, how do you devalue a bicycle without eliminating just what makes it a good, fun thing to ride? This is a frame that's been evolving into what might be called an "inverse hybrid", a new style monster uniquely suited for urban riding.

The bicycle industry currently pumps out some hideous beasts it calls hybrids, essentially overgrown mountain bikes designed to be ridden fully upright. Basically they make it easier to ride over potholes while sucking the joy out of every other aspect of urban bike riding. The inverse hybrid is the reverse, fixed gear gives you control and real sense of the road, while chopped riser handlebars put you in the ultimate urban riding position. Higher than the drop bars of a road bike, but lower and narrower than the chunky riser bars of a mountain bike. It handles almost like an overgrown BMX, if a BMX was capable of any real speed and efficiency on the city streets. It's a stance that gives a unique combination of maneuverability, visibility, hopping ability and just the right feel of the road in your hands.

The challenge now is to make an inverse hybrid that no one wants to steal. So just how do you make something that's only value is that it has no real value?

** This is particularly true at this time of year, the beginning of the fall and the end of the bike season. Odds are for a few months in the spring this bike will be more valuable than the sum of it's parts, only to lose that property as days begin to get shorter.

September 09, 2006

Emergence 06: Chris Downs

Chris Downs of livework :: service innovation & design talked about the evolution of his company as the first ever service design consultancy. A good talk, they do good work, not sure what I can add.

random notes:

"service envy"

"try and speak the language of business and not design"

"difference between systems design and service design"

"system is really efficient but the service really sucks"

"we design more products now as service designers then we did as product designers, but we design them from a service perspective"

Emergence 06: Jennie Winhall

I'm a pretty awful notetaker, I'd rather listen than write. The better the talk the less I write down. Jennie Winhall of RED gave an excellent talk on the work RED is doing in the UK with "Co-created services" in collaboration with various local government organizations. Plenty of info is up on their site.

RED currently is in the process of transitioning from an organization relying upon government funds into something... else. It will be interesting to see how that goes.

random notes:

"service that enables, rather and service that delivers"

"transformation design"

Emergence 06: Mary Jo Bitner

I'm out in Pittsburgh at Carnegie Mellon's Emergence 06 Conference, focused on Service Design.

The opening keynote is Mary Jo Bitner, Director for the Center for Services Leadership at Arizona State University.

The reason I'm here, and I suspect a healthy part of why this conference is being hosted by a design school, is due to a particular vision of services exemplified by the environmentally centered service vision exemplified by Interface Carpet and Paul Hawken. Bitner is a nice lead off as an explicit reminder that services are a far bigger, older and more staid world than the Hawken/Interface eco-revolution vision. She leads an institute firmly rooted in the business school and marketing world.

Coming from this space of academic business thinking, Bitner of course wants to talk about "innovation" in 2006. Unsurprisingly though nothing is particularly innovative about her talk and this is a good thing. Innovation is overrated and what Bitner has to offer is experience, a less exciting but far more valuable service. Service makes up as much as 80% of the economy in America, and according to Bitner yet service innovation lags significantly behind product innovation. It's probably true, but I have to wonder if that might have something to do with many services, hotels and restaurants for instance, have been evolving for thousands of years, while something like portable music players have at most a handful of decades behind them. The exact relationship between product innovation and service innovation was left unsaid. The airline industry can draw upon thousands of years of transportation services, yet at the same time many of it's core particulars are obviously dependent on airplane and airport technologies.

Bitner stresses that services are intangible (more on this later) and processes. She is also keen on pointing out that it's a very person driven industry, she quotes several CEOs talking about taking care of their employees, which somehow translates into taking care of the customers. The customers in Bitner's view are "in the factory", and studies apparently show that the more they get involved the more satisfied they are. Just how taking care of the employees translates into taking care of the customers is left unsaid and unproven.

September 05, 2006

The Abstract Dynamics Bookstore

Occasionally I've thought it might be a good idea to build up a little Abstract Dynamics bookstore of sorts using Amazon's rather powerful API and referral setup. But given how little money I've ever made off my experiments with their setup and given how much time it would take it has never happened. Until now, when Amazon decided to make it ridiculously easy to set up. So easy that it was live before I even really got to mull over the appropriateness of it all. Basically it's a store dynamically generated by Amazon using 9 of my selections as a base, it's an experiment do with it what you will, while I figure out if there is a way to get way past that nine selection limit...

August 29, 2006

The $300 Dollar Greens

A $300 dollar man was a draftee on the Union side of the US Civil War who opted to (and could afford to) pay a $300 fee in order to avoid military service. That's almost $6000 in today's dollars. Now imagine it's 1863 and you encounter a $300 man at a bar and get to talking and they start bragging about how much they are doing to fight against slavery. What would you think of such a person? Yeah, that's pretty much how I feel about this whole idea of "carbon neutral".

Sure the "$300 dollar greens" hearts might be in the right place, and there certainly are worse places their money can go, but just because it's cheap to buy off your conscious does not mean you can buy a real solution on the cheap, does it?

There are a whole lot of people out there in the world who just can not afford to go "carbon neutral". Would you rather help a person or plant a tree? That's a simple question with an infinitely complex answer, because helping the environment ultimately should help everyone on this planet is some small way. The health of the environment and the people who live in it are intricately tied together in ways more complex than we can easily untangle. Yet there is no doubt in my mind that an unhealthy chunk of the environmental movement is comprised of rich people buying a little peace of mind (aka ignorance) while protecting environments that most people in the world could never afford the carbon needed to visit, let alone afford to offset it somehow.

The bigger, more abstract and distant the problems, the easier it is to forget the real issues of inequality and poverty that stubbornly persist in the forgotten human environments of our own countries and cities. Yet as Majora Carter so intensely reminds us, these too are environmental problems. Hard problems, ones that won't go away by planting $300 worth of trees. Money is important, it can't be dismissed, but it can't be use to dismiss a problem either. These are problems that don't get solved by buying ugly lightbulbs, cramped cars and carbon offsets, they are problems that can only be solved by hard work, insight and maybe a little luck. So what are you doing with yourself and that $300?

August 18, 2006

The Value of Metcalfe's Law

For whatever reason Metcalfe's Law has been all popping up everywhere I look over the past 24 hours.

The July issue of IEEE Spectrum has an article "Metcalfe's Law is Wrong" that is probably the crystal under which all this attention can be formed.

Metcalfe's law basically states that a value of a network grows exponentially with the number of nodes. A telephone network with only one phone is worthless. One with two is usefully only to the few people who can reach those two phones. But a phone network with a million phones has a massive value. The authors of the IEEE article don't dispute the existence of "network effects", the fact that as nodes increase networks rapidly increase in potential value. What they dispute is the exponential math that Metcalfe, the inventor of Ethernet and founder of 3Com, uses. The authors instead argue for logarithmic growth, or something close to it. They are probably right.

They also make an important point that "Metcalfe's law" is not a law at all, but merely a empirical observation that serves as a useful guide for analysis. What they completely miss is the wide open flaw in Metcalfe's Law, which can be summed up in one word, value.